Fun with FGF21

...Did everyone just panic-buy an FGF21?

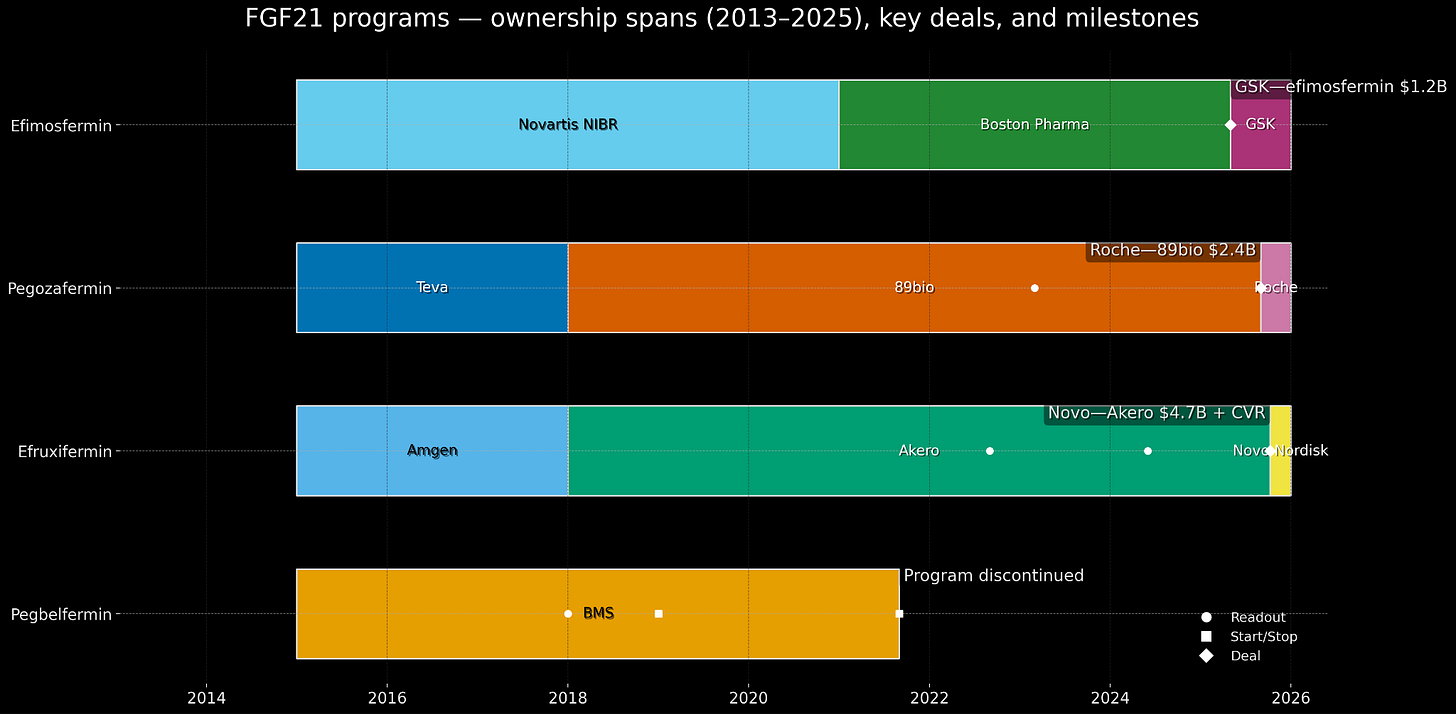

In September 2021, Bristol Myers Squibb discontinued development of pegbelfermin, a PEGylated version of a hormone called FGF21, after spending years and probably hundreds of millions of dollars testing it in patients with liver disease. The drug reduced 5-7 percentage points more than placebo and improved various biomarkers of liver damage. But in the trial that mattered, 24% of treated patients had fibrosis improvement versus 31% of placebo patients, which is not what you want. BMS said it would “pursue external opportunities” for the asset, which is corporate-speak for “we’re done here, maybe someone else wants to try.”

In May 2025, GSK paid $1.2 billion cash for efimosfermin from Boston Pharmaceuticals, a once-monthly FGF21 analog. Four months later, Roche paid $2.4 billion for 89bio and its pegozafermin, also FGF21. Three weeks after that, Novo Nordisk1 paid $4.7 billion for Akero Therapeutics and efruxifermin, also FGF21. In five months, large pharmaceutical companies deployed more than $8 billion to acquire what are, fundamentally, slightly different derivatives of the same hormone that BMS had walked away from in 2021.

This raises some questions. The efficient market hypothesis suggests that asset prices should reflect all available information. So either: (1) BMS was wrong in 2021 and left billions on the table, or (2) something changed between 2021 and 2025 that made these assets suddenly worth $8 billion, or (3) the acquirers in 2025 are overpaying and will regret this, or (4) these explanations each contain partial truth that reveals how drug development actually works.

Spoiler: it’s mostly option 4.

A Solution Looking for a Problem

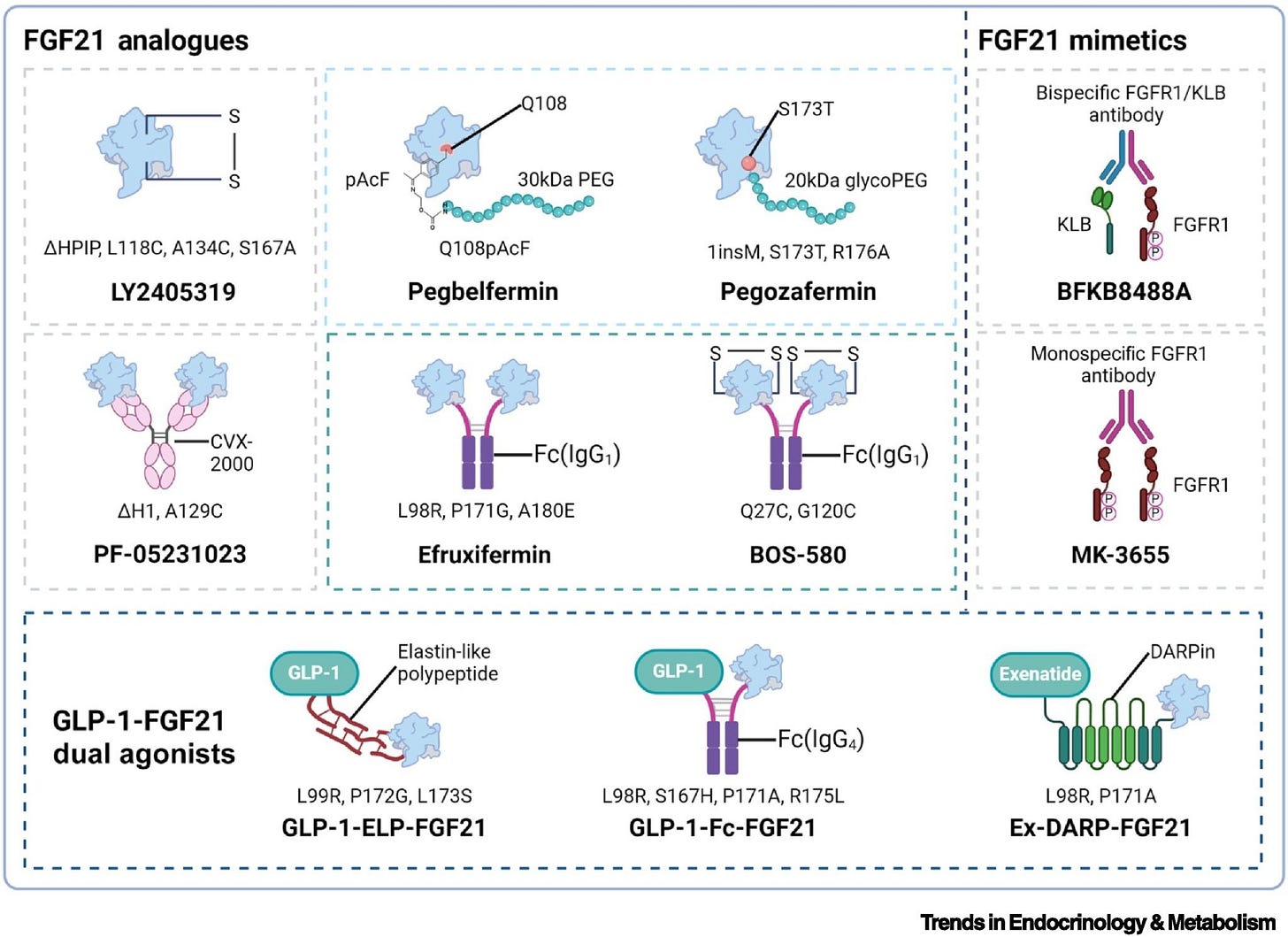

Fibroblast growth factor 21, better known as FGF21, is a protein hormone, about 181 amino acids long, that your liver makes when you’re fasting or metabolically stressed. It tells your fat tissue to burn more fat, your liver to be less insulin-resistant, and your brain to maybe stop eating so many carbs. In 2000, scientists at Eli Lilly discovered that if you give extra FGF21 to diabetic monkeys, they get healthier - better blood sugar, lower triglycerides, weight loss.

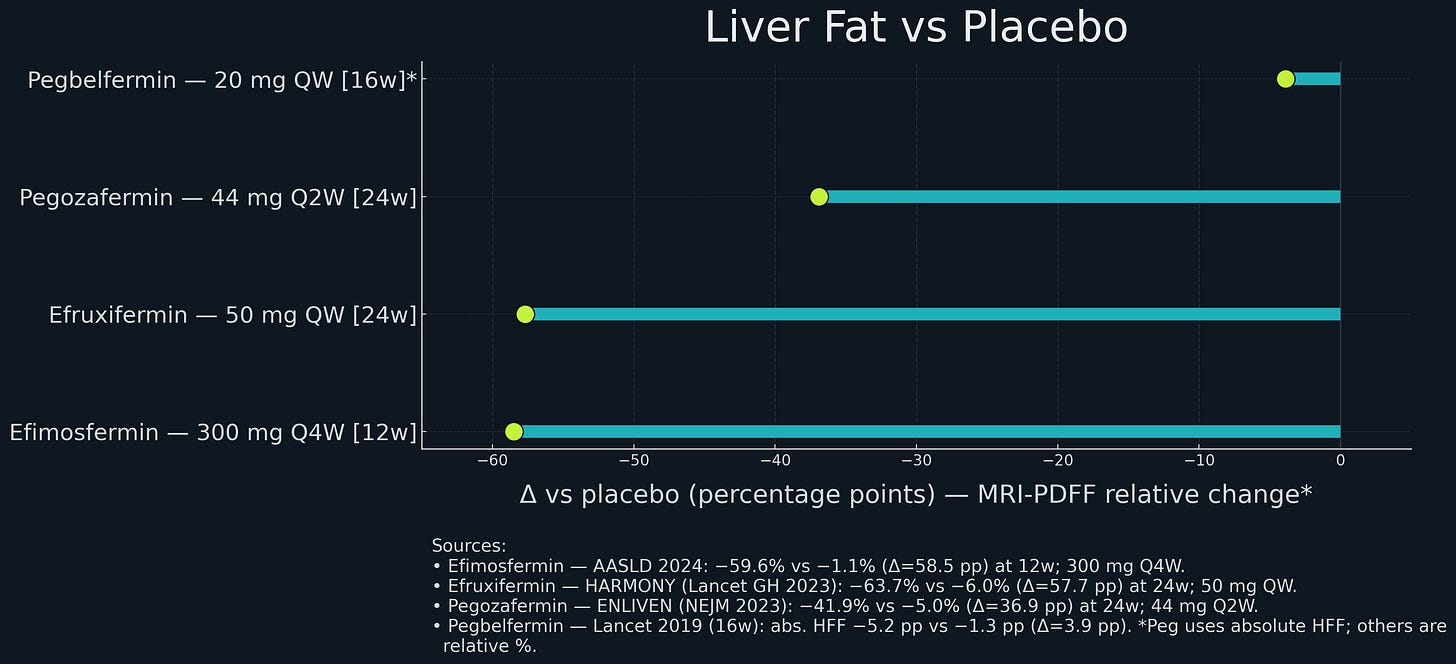

FGF21 has a half-life in human blood of approximately 90 minutes. Your kidneys clear it out fast, and various proteases degrade it even faster. If you want to use it as a drug, you’d need to inject it constantly. In early human trials, FGF21 analogs improved cholesterol but didn’t lower blood sugar or cause weight loss as dramatically as everyone hoped. By 2013, Lilly had tested an engineered variant in obese diabetic patients. It worked on lipids, but you had to inject it daily. Moreover - it didn’t have a statistically meaningful effect on blood glucose.

So Lilly shelved FGF21 for diabetes. The opportunity cost was too high. FGF21 became what venture capitalists call “a solution looking for a problem.”

But several companies kept tinkering with the molecule in their research labs (we’ll get to this later). This is a common pattern in biotech: the first company to try something often fails, but they generate data that helps the second company succeed.

The NASH Gold Rush and Subsequent Graveyard

Around 2015, a bunch of smart people simultaneously realized that non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) - fatty liver disease that progresses to inflammation and scarring - was going to be huge. The logic: obesity and diabetes are rising globally, around 5% of adults in developed countries have NASH, it can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure, and there are zero approved treatments. Analysts projected the NASH market at $35-40 billion by 2030.

2016 was peak NASH fever, with companies paying over $1 billion for Phase 2 assets with mixed data. BMS, having licensed pegbelfermin from Ambrx, pivoted it from diabetes to NASH. As we discussed earlier - FGF21 reduces liver fat, increases adiponectin (an anti-inflammatory hormone), and improves insulin sensitivity, which made the mechanistic rationale more than solid.

But NASH drug development is uniquely difficult:

Slow, variable disease: NASH takes decades to progress. To prove your drug prevents bad outcomes, you’d need a 10-year trial. So regulators like the FDA now accept surrogate endpoints (fibrosis improvement on biopsy), creating uncertainty about whether this translates to actual clinical benefit.

Multifactorial biology: NASH isn’t one thing. It’s metabolic dysfunction plus inflammation plus fibrosis. You might need to hit multiple pathways.

High placebo effect: In NASH trials, 10-20% of placebo patients show fibrosis improvement, probably because they’re enrolled in a trial, get counseling, and lose weight.

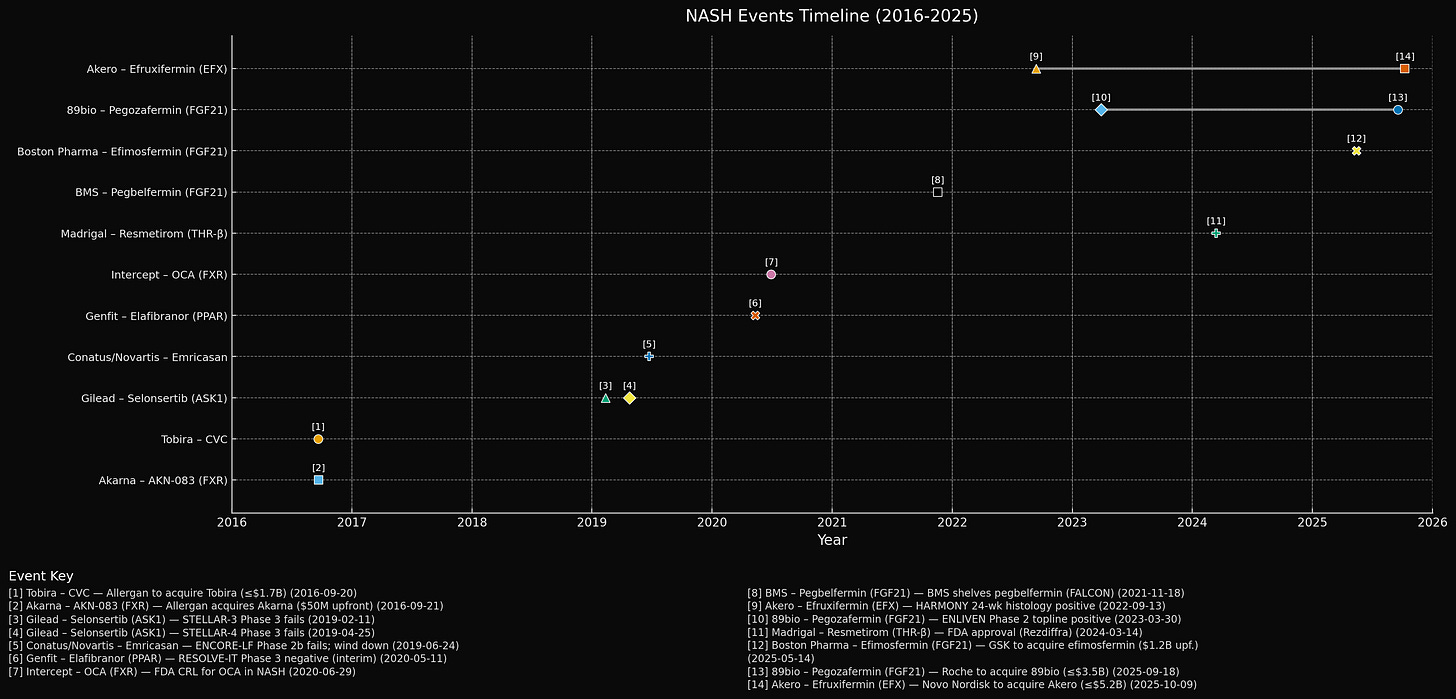

Between 2018 and 2021, most NASH drugs failed. Gilead’s selonsertib, Novartis/Conatus’s emricasan, Genfit’s elafibranor - all Phase 3 failures. Intercept’s obeticholic acid got rejected by the FDA despite modest fibrosis improvement. By mid-2020, investor sentiment on NASH had soured. Intercept’s stock fell 93% from its peak. Biotech analysts were writing gloomy things like “NASH has become a graveyard of failures.”

Pegbelfermin: Close But No Cigar

Into this environment, BMS reported results for pegbelfermin in 2021. Phase 2a data from 2018 (16 weeks) had shown promise: pegbelfermin reduced liver fat by about 5-7 percentage points more than placebo, decreased liver enzyme markers, and increased adiponectin 2-fold. Safety looked good.

The Phase 2b trials (FALCON 1 and FALCON 2, 48 weeks, 2019-2021) tested pegbelfermin in patients with advanced fibrosis (F3) and compensated cirrhosis (F4). The primary endpoint was at least one stage of fibrosis improvement with no worsening of NASH.

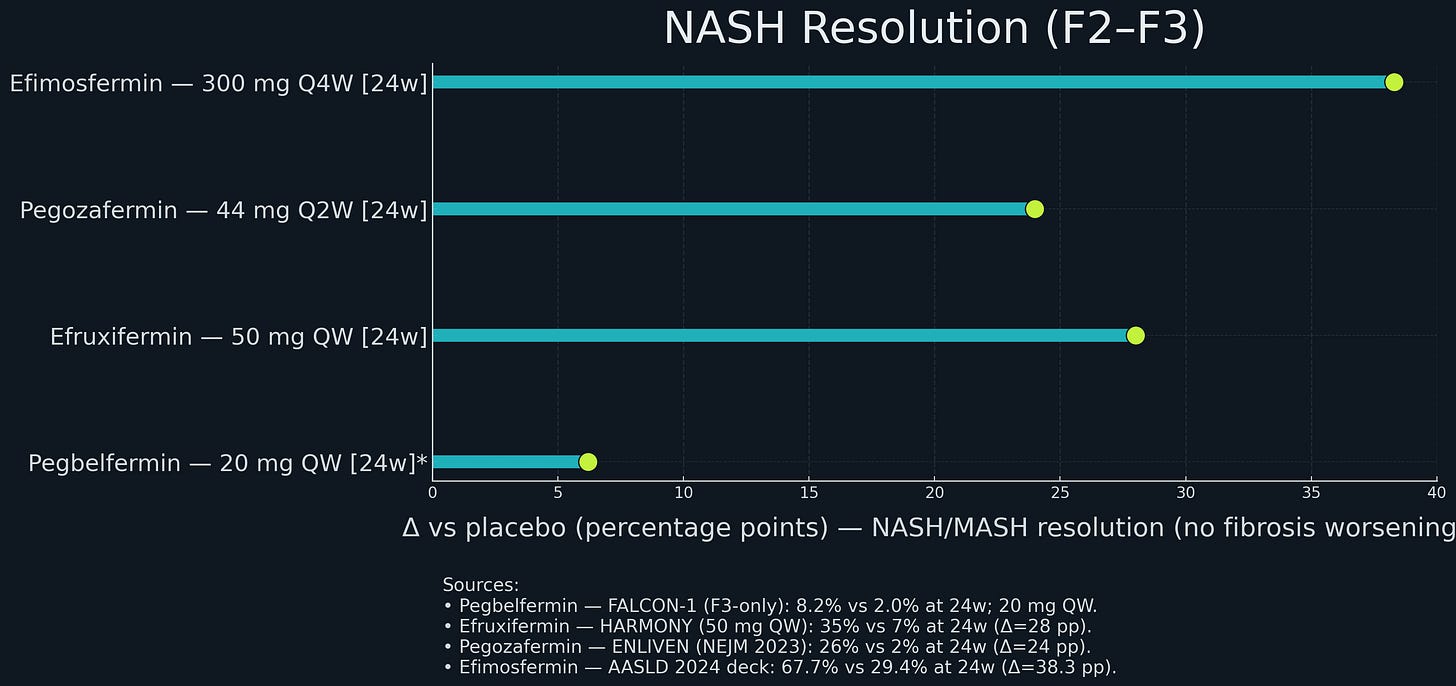

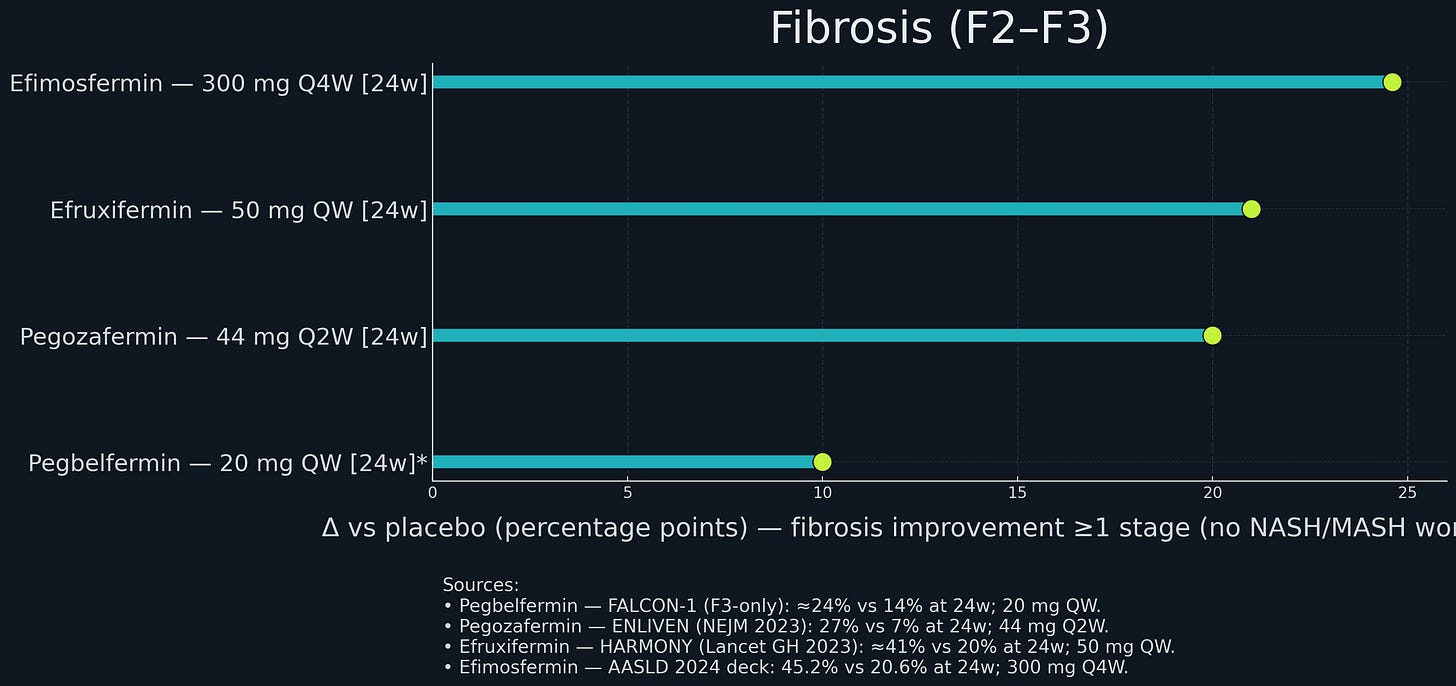

Results: Pegbelfermin did not beat placebo. In FALCON 1 (F3 patients), approximately 24% of pegbelfermin treated patients had fibrosis improvement versus 14% on placebo. Not statistically significant. In FALCON 2 (F4 patients), a similar story - no benefit. BMS consequently discontinued the program.

The Triumph of Incrementalism

While BMS was winding down pegbelfermin, three smaller companies - Akero, 89bio, and Boston Pharmaceuticals - were advancing their own FGF21 programs. All companies were founded around the same period of 2015 - 2018. raising modest Series A rounds (tens of millions, not hundreds). All three were working on second or third-generation FGF21 analogs for NASH as their flagship programs.

Akero’s efruxifermin (EFX): An Fc-FGF21 fusion protein originally developed at Amgen, with the stabilizing mutations including Pro171Gly. Half-life: ~75-85 hours. Dosing: weekly.

Akero ran a Phase 2b trial (HARMONY, 2020-2022) in patients with moderate fibrosis (F2-F3). Dose: 50 mg subcutaneously, once weekly, for 24 weeks.

At 24 weeks, efruxifermin achieved approximately 37% NASH resolution versus 9% on placebo (a 28 percentage point difference); and in a 96-week open-label extension, 75% of patients on EFX had fibrosis improvement, including many with at least two stages of regression.

Even more strikingly, in cirrhotic patients (F4), 29% had cirrhosis reversal to F3 or lower vs 12% placebo - the first time anyone had shown clinical evidence of cirrhosis reversal in a drug trial.

89bio’s pegozafermin: A PEGylated FGF21 analog originally developed at Teva, with the glycoPEG approach2 and similar stabilizing mutations including Pro171Gly. Half-life: ~55-100 hours, enabling once-weekly or every-two-weeks dosing.

89bio ran Phase 2 trials in NASH (ENLIVEN, 2022-2023) with F2-F3 patients.

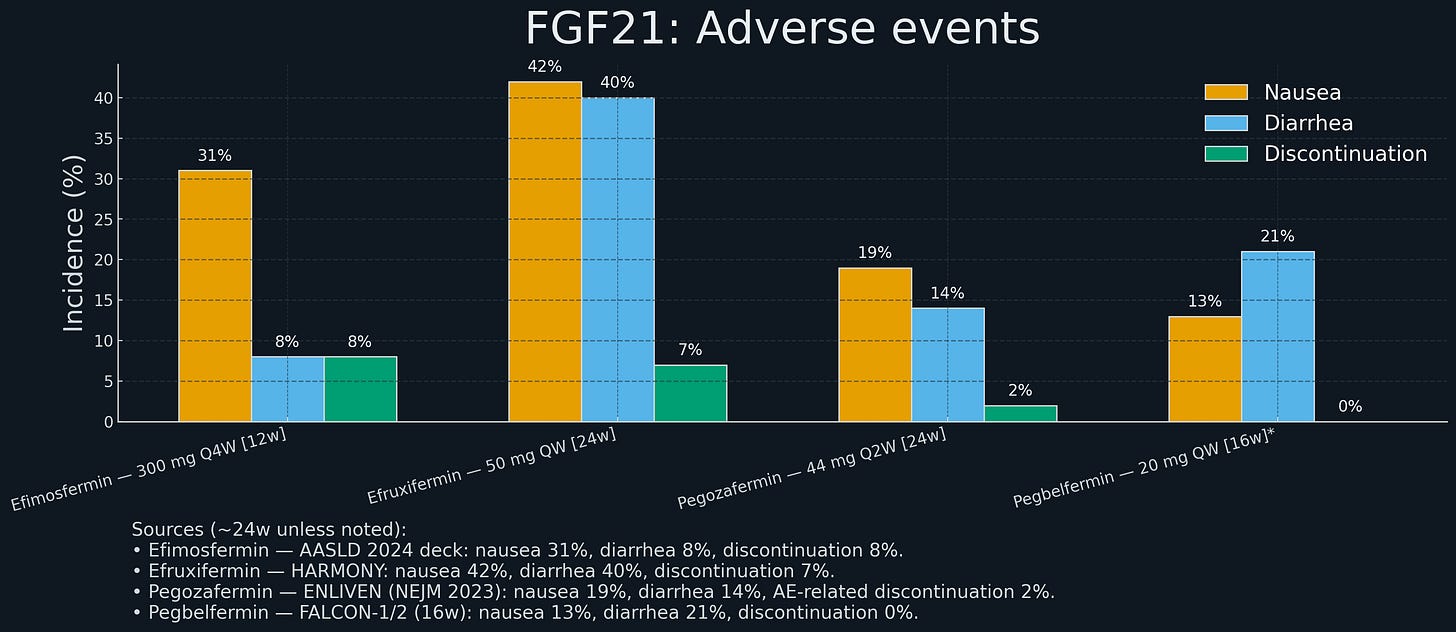

Pegozafermin was notably better tolerated than efruxifermin, with lower nausea and diarrhea rates (~9-21% vs ~21%), possibly because the every-two-weeks dosing created a flatter pharmacokinetic profile.

Boston Pharmaceuticals’ efimosfermin: An Fc-FGF21 fusion protein originally developed at Novartis’ NIBR and later in-licensed by Boston Pharmaceuticals. It incorporates stabilizing substitutions in the FGF21 core and is engineered for extended exposure, allowing once-monthly subcutaneous dosing.

Boston Pharmaceuticals ran a randomized Phase 2 study in patients with biopsy-confirmed NASH and stage F2–F3 fibrosis. After 24 weeks, 45% of treated patients achieved at least one-stage fibrosis improvement versus 21% on placebo; 68% achieved NASH resolution without fibrosis worsening versus 29% on placebo. The drug was well tolerated, with a low rate of treatment-related gastrointestinal events and minimal discontinuations.

Efimosfermin’s monthly dosing profile gives it a potential convenience advantage over weekly or bi-weekly FGF21 analogs - though the Phase 2 dataset remains smaller than that of Akero or 89bio.

Small Improvements Compound

The molecular differences between these drugs are actually pretty small - a few mutations and improved PEG chemistry. But those small changes translated into meaningfully better clinical outcomes.

The difference between “doesn’t work” and “works really well” came down to maybe 3 to 5 mutations and better PEGylation chemistry. This is a general lesson in drug development: marginal improvements in molecules can have non-marginal effects on clinical outcomes. And those marginal improvements often come from learning what didn’t work before. Pegbelfermin generated data that informed the design of pegozafermin and efruxifermin. BMS didn’t capture the value of that learning, but the industry did.

Resmetirom Changes the Game

In December 2022, while Akero and 89bio were presenting their Phase 2 data, another company - Madrigal Pharmaceuticals - announced that its NASH drug, resmetirom, had succeeded in Phase 3.

Resmetirom is a thyroid hormone receptor-β (THR-β) agonist - not related to FGF21 at all. The Phase 3 trial (MAESTRO-NASH, ~2,000 patients, 52 weeks) met both co-primary endpoints:

NASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis: 26% vs 9.7% placebo

Fibrosis improvement: 24% vs 14% placebo

In March 2024, the FDA approved resmetirom (brand name: Rezdiffra) as the first drug specifically for NASH with moderate-to-advanced fibrosis.

Why does this matter for FGF21 analogs?

Regulatory precedent: Resmetirom’s approval validated the FDA’s willingness to accept histological surrogate endpoints as a basis for conditional approval. This de-risked other NASH programs.

Commercial proof-of-concept: Resmetirom’s launch demonstrated a real market. Payers are covering it, doctors are prescribing it, patients are taking it. Revenue is ramping up (Madrigal is projected to gross over $500M in sales for this year - in only its second on the market).

Competitive context: Resmetirom’s placebo-adjusted fibrosis improvement rate (~10%) set a benchmark. Efruxifermin’s 28% and pegozafermin’s 27% looked better. Suddenly, FGF21 analogs weren’t speculative science projects - they were potential best-in-class drugs entering a validated market.

From a deal-making perspective, resmetirom’s approval in early 2024 was the starting gun. If you’re a big pharma company with no NASH asset, you’re looking at a situation where the market exists, FGF21 analogs have better Phase 2 data than resmetirom had, there are exactly three viable FGF21 programs available, they’re all small companies, and if you don’t buy one now, someone else will.

This is how bidding wars start.

The 2025 Feeding Frenzy

Deal #1: GSK licenses from Boston Pharma (May 2025)

GSK paid $1.2 billion upfront ($2.0B total with milestones) for efimosfermin, an Fc-FGF21 fusion originally from Novartis’ NIBR, similar to efruxifermin but with once-monthly dosing. Monthly dosing is attractive for a chronic disease like NASH - more convenient for patients, might improve adherence. Boston ran a Phase 2 trial showing fibrosis improvement rates comparable to efruxifermin (~25%, placebo adjusted) with good safety.

GSK gets strategic entry into metabolic liver disease (they had no presence), a Phase 3-ready asset, and potential dosing advantage (12x/year instead of 52x/year). The $1.2B upfront is less than what Roche and Novo paid, but efimosfermin is arguably less de-risked with a smaller Phase 2 dataset.

Deal #2: Roche buys 89bio (September 2025)

Roche historically dominated hepatitis C, then lost it when Gilead’s direct-acting antivirals cured hep C in 8-12 weeks. By 2022, Roche was looking for new growth drivers in liver disease.

89bio was an obvious target. Pegozafermin showed strong Phase 2 data in NASH (27% fibrosis improvement) and severe hypertriglyceridemia (57% TG reduction). The dual indication strategy means pegozafermin could address both NASH and a significant cardiovascular risk factor, expanding the commercial opportunity. Every-two-weeks dosing might be better tolerated than weekly.

Roche paid $2.4 billion upfront ($3.5B total with milestones) - the $14.50-per-share cash offer represented about a 52% premium to the 60-day VWAP.

Deal #3: Novo Nordisk buys Akero (October 2025)

Novo is the global leader in diabetes and obesity (semaglutide/Ozempic/Wegovy). They’ve been printing money from GLP-1 agonists. But semaglutide is great at NASH resolution (via weight loss) while not significantly improving fibrosis on its own. In a 72-week Phase 2 trial, semaglutide achieved ~60% NASH resolution but fibrosis improvement was not significantly better than placebo.

Novo’s strategic answer: pair semaglutide (for metabolic/weight) with an FGF21 analog (for fibrosis).

To date, Akero has had the most impressive fibrosis data in the field: 21% net improvement at 24 weeks, and a staggering 49% at 96 weeks - the first evidence of cirrhosis reversal among the FGF21s. Novo’s CEO stated publicly he was “super excited” about FGF21 analogs as “cornerstone therapy, alone or together with semaglutide.”

On October 9, 2025, Novo announced the acquisition: $4.7 billion cash plus a $6 CVR per share (~$500 million) - a total potential value of $5.2 billion. The $54-per-share cash offer equates to ~19% over a 30-day VWAP (likely lower than Roche’s premium due to run-up / speculation before deal announcement).

The combination opportunity is where it gets interesting. If efruxifermin (fibrosis driver) plus semaglutide (metabolic driver) becomes standard of care for metabolic liver disease:

Semaglutide for obesity/T2D: ~$13,000/year

Efruxifermin for fibrosis: ~$20,000/year

Total: ~$33,000/year per patient

Now Novo owns both drugs, capturing the entire $33K. Even with just 500,000 patients, that’s $15 billion in annual revenue. There’s also a defensive element: if Novo hadn’t bought Akero, someone else would have, then partnered with Lilly or another GLP-1 maker to create a competitive combo.

So… What Actually Changed Between 2021 and 2025?

BMS walked away from pegbelfermin in 2021. Three and a half years later, functionally similar molecules are worth $8 billion. What changed?

1. The molecules actually got better (incremental innovation)

Efruxifermin, pegozafermin, and efimosfermin are better engineered molecules - better protease resistance, better PK, better dosing. The molecular improvements are incremental, but their clinical impact is substantial. If pegbelfermin was worth $0 in 2021 and pegozafermin is worth $3.5B in 2025, you’re implicitly valuing a few mutations and 30-40 hours of extra half-life at $3.5 billion.

That seems extreme, which suggests a more nuanced explanation: pegbelfermin wasn’t worth $0 in 2021. It had value - maybe $500M-$1B - but BMS didn’t want to deploy the capital and risk to test it further (in a more specific patient population/at a different dose/in a combination/etc), and no other company was willing to buy it at a price that made sense for BMS.

2. Regulatory and commercial de-risking (resmetirom)

Before resmetirom’s approval in March 2024, NASH was a speculative indication. No one knew for sure if the FDA would approve drugs based on histological surrogates, or if payers would cover them. Resmetirom eliminated most of that risk.

A rough calculation: Say in 2021, the probability of a NASH drug getting approved was ~30%. In 2025, post-resmetirom, it’s ~70%. If peak sales are $4B:

2021: 30% * $4B = $1.2B risk-adjusted NPV

2025: 70% * $4B = $2.8B risk-adjusted NPV

That’s a $1.6B increase just from de-risking.

3. Superior clinical data changed the probability distribution

Pegbelfermin’s Phase 2b: 24% vs 31% fibrosis improvement (not significant). Even if you believed FGF21 could work, you’d rationally be skeptical about pegbelfermin specifically.

Efruxifermin’s Phase 2b: 4% vs 19% (highly significant). The magnitude of effect (30 percentage point difference) suggests a robust treatment effect unlikely to disappear in Phase 3. Similarly, pegozafermin’s 27% vs 7% is convincing.

Better data leads to higher probability of success leads to higher valuation.

4. Competitive dynamics and scarcity

By late 2024, there were exactly three credible FGF21 programs available for acquisition. Once GSK bought Boston in May 2025, there were two. Once Roche bought 89bio in September, there was one. Novo grabbed it in October. Plausibly scarcity dynamics at play, given the timing of it all.

5. The combination therapy narrative

In 2021, combination therapy for NASH was a nice idea but unproven. By 2025, it’s becoming consensus. GLP-1 agonists address metabolic drivers but not fibrosis. FGF21 analogs address fibrosis but don’t cause dramatic weight loss. Together, they’re complementary.

Novo’s acquisition makes sense only if you believe in combos. Efruxifermin alone might be a $3-4B product. Efruxifermin plus semaglutide together could be a $10-15B franchise.

6. Market size expansion

In 2021, the addressable NASH population was ~5-10 million patients in the US (F2-F4). By 2025, with safe effective drugs, you might treat F1 patients to prevent progression, doubling the addressable population. Pegozafermin works in severe hypertriglyceridemia (another 500K patients).

If the addressable market is 2-3x bigger than previously thought, peak sales increase proportionally, and so does the acquisition price.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis, Revisited

The EMH says asset prices reflect all available information. In a strong-form EMH world, pegbelfermin’s value in 2021 should have been ~$0 if it truly didn’t work, and efruxifermin’s value should have been ~$3-5B if it was going to succeed.

Obviously, that’s not what happened. In 2021, pegbelfermin was discontinued (implied value $0) and efruxifermin was worth maybe $500M (Akero’s market cap). By 2025, efruxifermin is worth $5.2B. Most of this value crystallized in a very short window after all the uncertain factors from 2021 resolved positively.

This is not efficient market behavior in the strong sense. This is more like a phase transition: the market was in a “NASH is too hard, FGF21 doesn’t work” equilibrium from 2018-2021, then abruptly shifted to a “NASH is solvable, FGF21 is the answer” equilibrium in 2023-2025. The companies that bought in after the transition paid full price. BMS, which sold out before the transition, got nothing.

By mid-2021, a diligent investor could have identified the mispricing. The mechanistic upgrades were sitting there in public filings: second-generation FGF21 analogs had FAP-resistance mutations (P171G) and Fc-fusion that fixed the exact cleavage and half-life problems that doomed pegbelfermin. And there was actual human data - efruxifermin’s BALANCED trial showed large liver-fat reductions and histology improvements, while 89bio’s pegozafermin independently did the same thing, which meant this was real biology and not just one lucky molecule.

Better yet, there was a playbook. Published papers had linked >= 30% PDFF reduction to histologic response, so you could translate “fat goes down at 12 weeks” into probabilistic expectations for “fibrosis improves at 52 weeks.” The FDA had already published a draft guidance suggesting that histology endpoints were acceptable for accelerated approval back in 2018. The regulatory path existed.

And the indication was about to get validated anyway. Resmetirom - a completely different mechanism - had good Phase 2 data and was in Phase 3, which meant NASH was going to be a real drug category soon regardless of what happened to FGF21. Meanwhile everyone was freaking out because pegbelfermin failed in November 2021, but that was a first-gen construct without the fixes. It told you nothing about the better-engineered molecules that already had positive data.

All the pieces were there. The market just hadn’t put them together yet. Most investors anchored on recent failures and didn’t differentiate between “first-gen analog failed” and “entire class is doomed.” This created the mispricing that the 2025 feeding frenzy eventually corrected.

Biotech markets are not efficient in real-time. They’re efficient in retrospect. Information takes time to diffuse, narratives take time to shift, and cognitive biases distort valuations.

Smart investors and pharma companies can exploit this, but it requires deep scientific understanding (knowing that Pro-171 mutations matter, that Fc-fusion extends half-life), contrarian thinking (being willing to bet on NASH when everyone else had given up after pegbelfermin), and patience (waiting 3-5 years for clinical data to accumulate and the market to come around). Few possess all three - which is precisely why the mispricing exists.

The FGF21 story shows that in biotech, value is not created smoothly or fairly. It accrues to those who persist through the “nobody cares” phase, who iterate when others quit, and who are positioned correctly when the narrative flips.

For 20 years, nobody wanted FGF21. Then, suddenly, everyone did. That’s the story.

In a delicious bit of irony, Novo earlier this year had its own FGF21 program (zalfermin) discontinued in 2025 after Phase 1 trials showed it wasn’t good enough. Apparently $4.7 billion to buy someone else’s FGF21 was cheaper than making theirs work.

Plot twist - Novo Nordisk owns the IP rights (acquired from Neose Technologies in 2012) to the glycoPEGylation technology that Teva used to engineer pegozafermin. So Roche paid $2.4 billion for a drug that uses Novo’s proprietary PEG chemistry, then three weeks later Novo bought Roche’s competitor. Hilarious.

Lets also not forget the strong human genetic evidence of FGF21 with both liver enzymes & triglycerides. e.g. this 2022 paper https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0026049522002074

The fact that efruxifermin originated at Amgen makes this story even more interesting from a corporate strategy perspective. Amgen developed the Fc-FGF21 fusion and the Pro171Gly stabilization, then let Akero aquire it and advance it to approval, only for Novo to pay $5.2B for what was essentially Amgen's own molecule. This is a classic case of big pharma underestimating an asset's potential and leaving billions on the table when a nimbler biotech proved the value.