How Amgen Lost The PCSK9 Patent War

In 2014, Amgen sued Sanofi and Regeneron to claim ownership of an entire class of cholesterol drugs. Nine years later, the Supreme Court ruled against them - but they won where it mattered most.

Patent law rests on a simple covenant: inventors reveal their secrets, and society grants them temporary monopolies in return. But some companies want the monopoly without the showing. They want the treasure. They don’t want to draw the map.

In 2014, Amgen had developed evolocumab—a protein comprising 1,328 amino acids arranged with such precision that changing even one could eliminate its function entirely. This antibody binds to PCSK9, a protein that destroys the liver’s cholesterol-clearing receptors, and block its activity completely.

Amgen filed patents describing evolocumab in exhaustive detail. Twenty-five additional antibodies followed—all synthesized, all tested, all real. Then they claimed ownership of millions more they had never made.

That claim would soon be tested. Three thousand miles away, Regeneron had developed an entirely different antibody called alirocumab. Different sequence, different structure, different discovery method. It blocked the same protein.

The FDA blessed both drugs within twenty-eight days that summer of 2015—a bureaucratic miracle that should have marked the triumph of competitive innovation. Instead, Amgen was making the opening moves to an enormous legal assault——one that had begun the prior autumn. Nearly a decade later, nine Supreme Court justices would determine whether building a mousetrap grants you dominion over every possible way to catch a mouse.

Two Paths to the Same Summit

To understand what Amgen was claiming, we need to venture briefly into the cellular processes where this story unfolds.

Picture the liver cell as a recycling facility where LDL receptors serve as loading docks, constantly pulling cholesterol particles from the bloodstream for processing and disposal. PCSK9 functions as a quality control mechanism in this system. Its job—refined over millions of years of evolution—is to bind these receptors and mark them for destruction. When food was scarce and humans faced frequent starvation, this made evolutionary sense. PCSK9 helped conserve every molecule of cholesterol during lean times.

But evolution optimizes for survival to reproductive age, not for the convenience of modern medicine. In a world of drive-throughs and desk jobs, PCSK9’s cholesterol-conserving function has become a liability, contributing to the plaques that trigger heart attacks and strokes.

The protein’s importance emerged through one of biology’s elegant accidents. In the early 2000s, researchers had found genetic lottery winners—a French-Canadian family with naturally inactive PCSK9 who maintained cholesterol levels below 50 mg/dL and remarkably clear arteries well into old age.

This natural experiment provided the kind of proof that pharmaceutical executives dream about: blocking PCSK9 could prevent cardiovascular disease safely and dramatically.

Amgen was quick to capitalize: by 2007, they had developed evolocumab, an antibody against PCSK9. But while their scientists perfected the drug, their patent attorneys crafted a strategy of breathtaking scope. The patents covered any antibody that would bind to specific PCSK9 regions and block its function—defined not by biological architecture but by biological effect.

This created a fundamental problem. Amgen had synthesized just twenty-six antibodies and provided detailed information for each. Yet their patents claimed rights to potentially millions of different molecules—a clear violation of patent law’s core requirement that inventors describe their inventions sufficiently for others to reproduce them.

The inadequacy was glaring. Amgen’s guidance amounted to research assignments rather than manufacturing instructions. Their “roadmap” described standard practices already available to any researcher. Their “conservative substitution” methods provided no reliable way to predict which modifications would work.

This strategy was about to face its first real test. Three thousand miles away in Tarrytown, Regeneron had independently developed a different PCSK9 antibody called alirocumab. Alirocumab was developed using an entirely different approach. Instead of screening synthetic candidates, Regeneron had genetically modified mice to produce fully human antibodies in response to immunization with the PCSK9 protein.

Regeneron’s independent discovery exemplified the crux of how Amgen’s patent strategy was flawed. Developed using completely different technology, alirocumab shared no structural features with evolocumab beyond basic antibody architecture. Yet because it bound roughly the same PCSK9 regions, it fell within Amgen’s expansive claims.

Amgen had built one road to the summit and claimed ownership of the entire mountain. Now they discovered someone else had been climbing from the other side.

From Delaware to the Federal Circuit

The first battle erupted in Wilmington, Delaware, in March 2016. For a single week, expert witnesses attempted to explain protein folding and molecular binding to twelve ordinary citizens. It was like asking a jury to navigate a space mission based on rocket science they were learning in real time.

Amgen portrayed themselves as pioneers who had provided sufficient guidance for others to develop competing antibodies. They emphasized their enormous investment—billions over nearly a decade. Without broad protection, they argued, companies would abandon such research entirely.

Sanofi and Regeneron argued the claims lacked adequate written description and enablement. Their experts explained that antibody discovery is unpredictable—you must make and test candidates to know where they bind. Many different antibodies could meet Amgen’s claims while having vastly different structures, yet the listed sequences were insufficient to represent this full scope. Real-world evidence contradicted Amgen’s enablement theory——if their disclosure truly taught the art, why did Regeneron require years of independent research and proprietary platform development to reach the same therapeutic target?

In a stunning upset, the jury delivered complete victory for Amgen. Judge Sue Robinson’s subsequent ruling proved even more devastating: a permanent injunction ordering Sanofi and Regeneron to cease all sales of alirocumab over the lifetime of the Amgen patents. The injunction would have effectively created a complete monopoly, leaving patients with a single treatment option at whatever price Amgen chose to charge.

But Amgen’s victory proved short-lived. Just months later, the Federal Circuit granted an emergency stay in February 2017, and by October, the appellate court had delivered a dramatic reversal.

The difference lay in technical sophistication. Where the jury trial had stumbled through complex patent law, the Federal Circuit approached the case with precision, identifying a fundamental error in the jury instructions. The trial judge had asked jurors whether Amgen’s patents enabled some antibodies within their claims—the wrong question entirely. The real issue was whether they enabled the full breadth of what Amgen sought to monopolize.

The February 2019 retrial featured the same evidence but corrected legal standards. More damaging to Amgen’s case, their own experts now testified that modifying individual amino acids frequently eliminated an antibody’s function—undermining any claim that knowing a few examples could predict millions of functional variants.

The second jury reached a mixed verdict, but it was Judge Richard Andrews who delivered a decisive blow in August 2019. In an thirty-four-page analysis, he systematically invalidated all of Amgen’s asserted patent claims.

Most damaging to Amgen’s position, Andrews found that their own experimental data contradicted claims of adequate disclosure. As it turned out, Amgen had screened thousands of antibody candidates with failure rates exceeding ninety percent. If Amgen itself—with unlimited resources and years of experience—had failed in the vast majority of their attempts, how could their patents possibly enable others to generate millions of claimed antibodies?

Two years later, the Federal Circuit’s February 2021 decision definitively rejected Amgen’s final appeal. Every federal judge who had examined the enablement question in detail had reached the same conclusion: Amgen’s patents claimed far more than they had disclosed or enabled.

Hail Mary at The Supreme Court

Amgen’s petition for Supreme Court review represented a final attempt to reshape biotechnology patent law fundamentally. The company argued that strict enablement requirements would discourage investment in high-risk research areas where breakthrough innovations require enormous resources and face uncertain outcomes.

The Court’s decision to hear the case surprised observers who expected the justices to decline review of what appeared to be a technical patent dispute between pharmaceutical companies. The acceptance signaled recognition that fundamental questions about innovation policy and patent scope were at stake.

As the case approached the Supreme Court, major pharmaceutical firms began choosing sides. The battle lines resembled Napoleonic Europe—great powers aligning according to strategic interest rather than natural affinity.

The Amgen Coalition formed around broad patent rights for pioneering discoveries. AbbVie warned that strict enablement “chills investment in new discoveries.” GlaxoSmithKline argued that innovators faced an impossible trap: “Either she discloses her secrets for a narrow patent... or else her broad patent is invalidated.”

The Anti-Amgen League proved equally formidable. Pfizer led the opposition, arguing that patents “like Amgen’s violate the patent bargain by allowing patentees to obtain a monopoly on products without disclosing how to make them.” Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, Genentech, and Eli Lilly joined the core alliance. These companies asserted that their long-term interests lay in preventing any firm from claiming entire therapeutic territories based on minimal contributions.

The legal question turned on enablement under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a): had Amgen described their invention in sufficient detail to enable a person skilled in the art to make and use it? Courts apply the Wands factors—considering claim breadth, predictability, working examples, and experimentation required. The Supreme Court would decide whether the Federal Circuit correctly found Amgen’s disclosure inadequate for the scope they claimed.

During oral arguments, Justice Neil Gorsuch focused on patent law’s historical development and core principles. He questioned whether Amgen’s functional claiming approach was consistent with centuries of precedent requiring patents to teach how to make inventions rather than merely describing desired results.

Justice Elena Kagan explored the practical implications of Amgen’s position, asking why the company had not actually synthesized all four hundred antibodies it claimed if the process was as routine as their counsel suggested. Justices Sonya Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson pressed Amgen’s counsel on the mathematical relationship between disclosure and claimed scope, questioning how twenty-six examples could possibly enable millions of different molecules.

Defeat at Waterloo

The Court killed Amgen’s case in May 2023. Nine justices - no dissent. The message was clear. Justice Gorsuch’s opinion for a unanimous Court grounded the decision in patent law’s essential bargain: inventors receive temporary monopolies in exchange for disclosing their inventions sufficiently to advance human knowledge.

This bargain requires that patent claims be commensurate with disclosure—inventors cannot claim more than they have enabled others to make and use. Gorsuch traced this principle through centuries of American patent law, citing cases involving telegraphs, light bulbs, and other foundational technologies where courts had rejected attempts to claim broad functional monopolies without corresponding disclosure.

The telegraph case O’Reilly v. Morse proved particularly instructive. Samuel Morse had attempted to claim all methods of using electromagnetism for long-distance communication—far broader than the specific telegraph system he had actually invented and disclosed. The Supreme Court rejected this expansive claim while upholding narrower patents on Morse’s specific apparatus.

Justice Gorsuch found these historical precedents directly applicable to Amgen’s situation. Like Morse, Amgen was seeking to “monopolize an entire class of things defined by their function” while providing concrete guidance for only a small fraction of that class.

Most memorably, the Court articulated the principle that “the more one claims, the more one must enable.” This elegant formulation captured patent law’s fundamental requirement that broad claims must be supported by correspondingly broad disclosure—you cannot claim the entire forest while mapping only a single tree.

Applied to Amgen’s patents, this principle was devastating. The unanimous nature of the ruling—with all nine justices agreeing despite their different judicial philosophies—demonstrated the strength of the legal principles involved and the weakness of Amgen’s position.

Aftermath

Despite winning every appeal and securing a unanimous Supreme Court victory, Sanofi achieved a devastating financial loss through the simple expedient of delay.

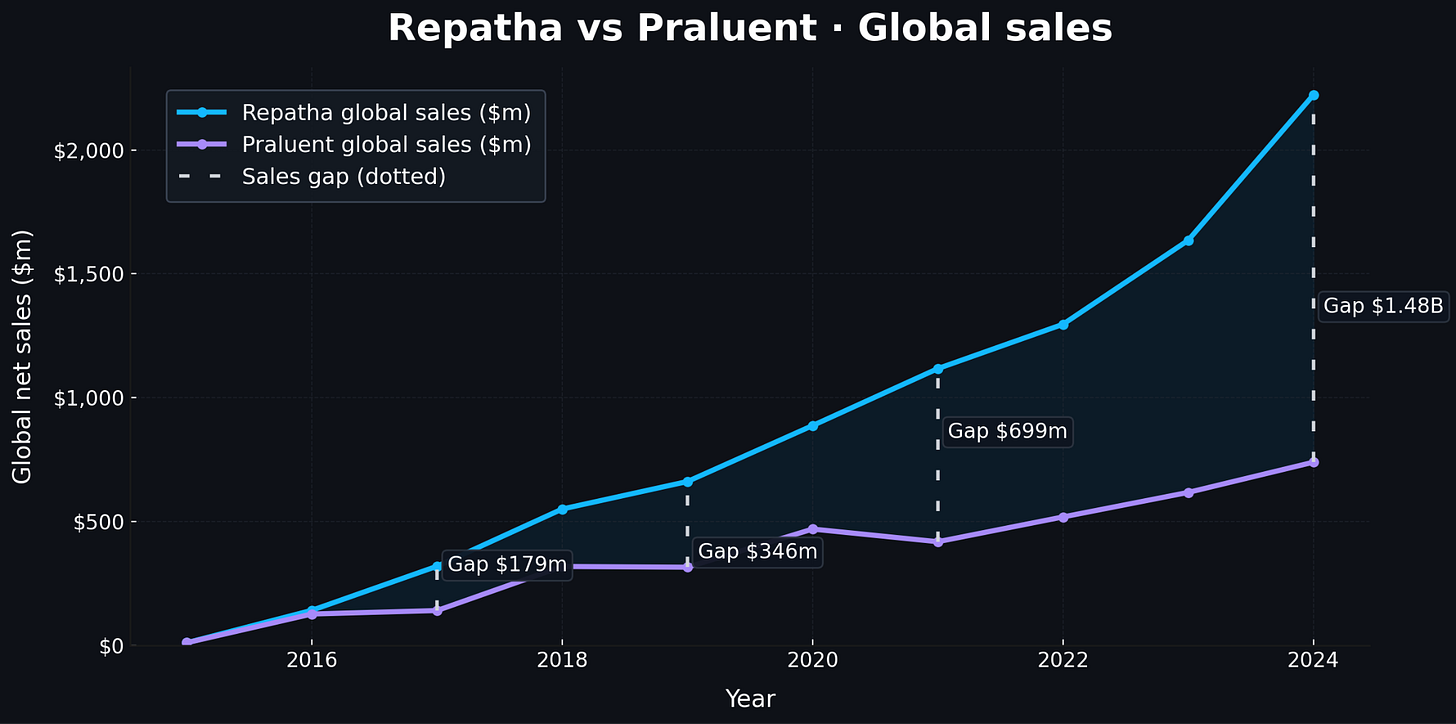

Their legal triumph masked a commercial catastrophe that reveals why rational executives pursue litigation even expecting ultimate defeat. During the critical launch years of 2016-2017, legal uncertainty clouded alirocumab’s market position while Amgen captured advantages that would compound over time1. In 2016, evolocumab generated $141 million in global sales versus alirocumab’s $116 million globally—a modest difference reflecting physicians’ caution about both revolutionary drugs. But by 2017, with a permanent injunction granted though stayed pending appeal, the gap widened dramatically. In 2019, evolocumab reached $661 million in global sales while alirocumab managed only ~$300 million.

Why invest in training staff and developing treatment protocols for a drug that might disappear from the market? By 2023, as the case reached the Supreme Court, the commercial disparity had become enormous. Evolocumab generated $2.2 billion globally while alirocumab managed approximately $740 million—a gap approaching $1.5 billion annually.

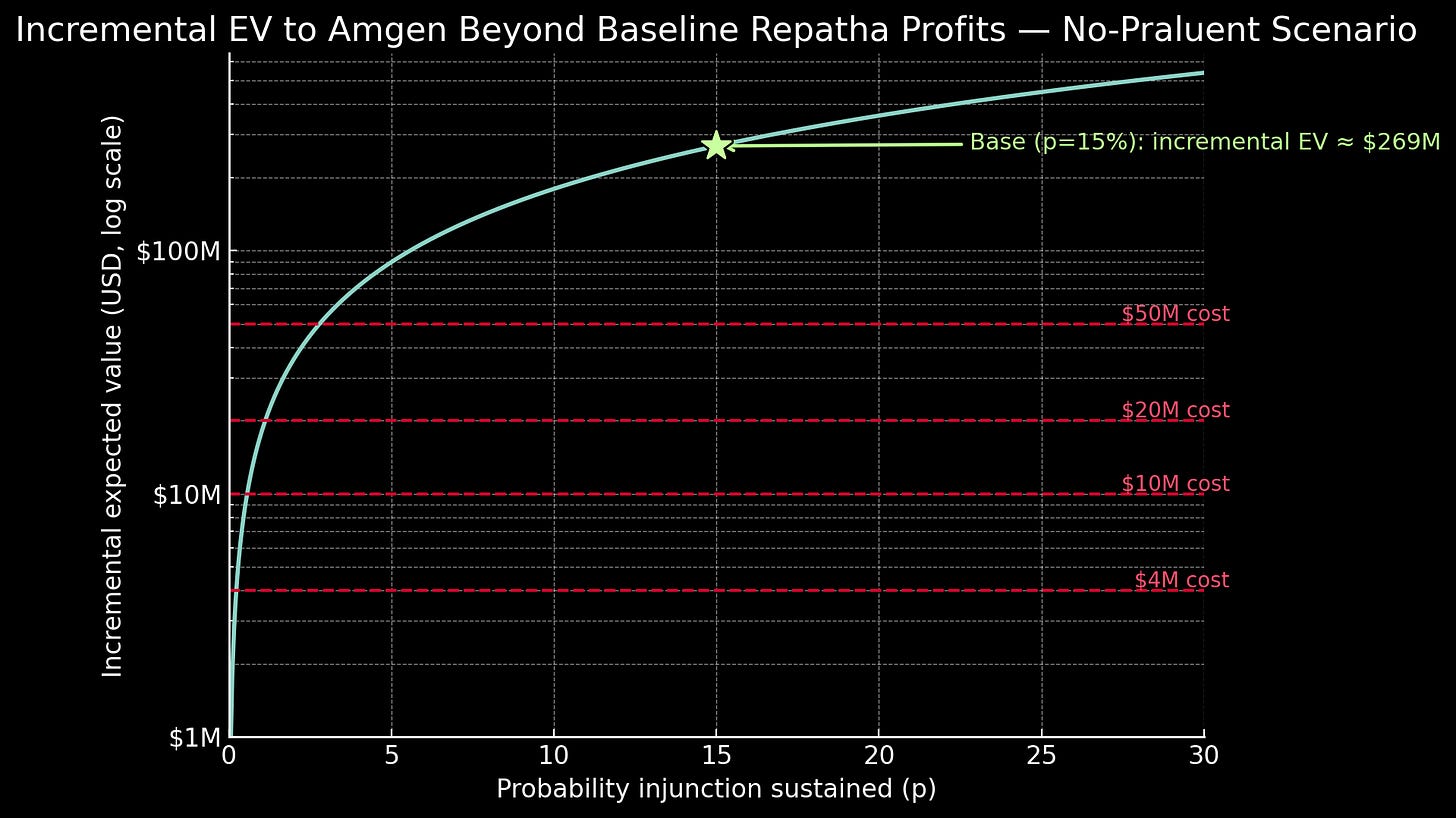

Their strategy wasn’t merely about delay, however. Amgen sought complete exclusion, and the January 2017 permanent injunction proved total victory was legally plausible. Using conservative assumptions, permanent exclusion would have generated roughly $336 million per year over an eight-year patent term. Even with only a fifteen percent probability of sustaining exclusion through appeals, this option value contributed approximately $270 million to the litigation’s expected value. Against litigation costs of perhaps $20 million, the financial logic was overwhelming2.

But the competitive market demonstrated benefits that transcended individual company profits. Both drugs launched with list prices exceeding $14,000 annually—costs that severely limited patient access despite revolutionary efficacy. Competition changed everything. Under sustained pressure, Amgen announced a permanent sixty percent U.S. price reduction to approximately $5,850 annually in 2018. Sanofi quickly matched this U.S. pricing.

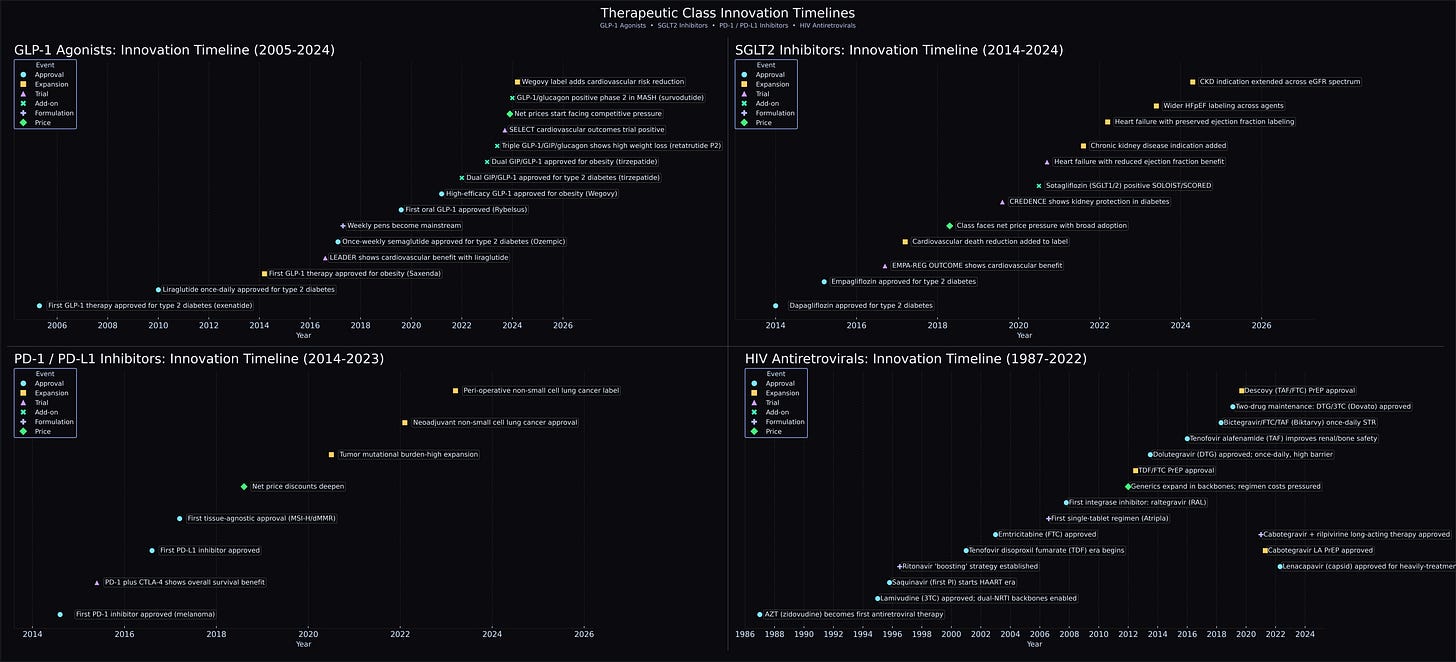

These reductions led to dramatically improved insurance coverage and reduced patient cost-sharing. By 2024, most major Part D plans covered either drug, enabling broader access to breakthrough therapy. Competition also spurred continued innovation; Novartis entered with inclisiran, offering twice-yearly injections instead of monthly treatments. Other companies began exploring gene editing approaches for potentially one-time cures.

This therapeutic diversity would have taken longer to emerge if Amgen had their way. By 2024, the combined PCSK9 inhibitor market approached $3.7 billion globally.

For Amgen, the antitrust consequences proved more tangible in financial consequences than the patent defeat. Regeneron alleged that Amgen executives coordinated to eliminate alirocumab’s market position “by hook or crook” after litigation failed, implementing bundling schemes that increased costs for pharmacy benefit managers selecting alirocumab over evolocumab. In May 2025, a federal jury awarded Regeneron $135 million in compensatory damages plus $271 million in punitive damages—over $400 million total.

The verdict represented war reparations––only perhaps too small a sum and too late a time––for Amgen’s failed attempt to monopolize the market through both patent and anticompetitive strategies.

Beyond the PCSK9 Patent War

We’ve spent considerable time dissecting Amgen’s failed legal strategy, but here’s the uncomfortable truth: if you were sitting in those Thousand Oaks boardrooms, you probably would have made the same call. The NPV mathematics we just scrutinized made the litigation inevitable. Even with a fifteen percent chance of sustaining a permanent injunction, the expected value exceeded two hundred million dollars against litigation costs of perhaps seven to eight figures. Odds are, they don’t even regret what they did.

But Amgen deserves credit beyond the cold financial calculus. When they committed hundreds of millions to PCSK9 inhibitors, the target remained genuinely speculative. While other companies recognized the opportunity, Amgen executed where they hesitated3. They ran the trials that proved PCSK9 inhibition could safely reduce cardiovascular events. That kind of pioneering work deserves substantial reward.

But empirical evidence reveals why blocking follow-on competition carries enormous costs. A USC Schaeffer Center analysis published last year found that follow-on drugs earn the largest market share in more than half of classes studied. New approaches appear. Follow-on competition compresses the search time for better therapies: better safety profiles emerge. More convenient dosing arrives. The efficacy ceiling grows taller. New indications are discovered and new uses for other unmet needs are discovered more quickly.

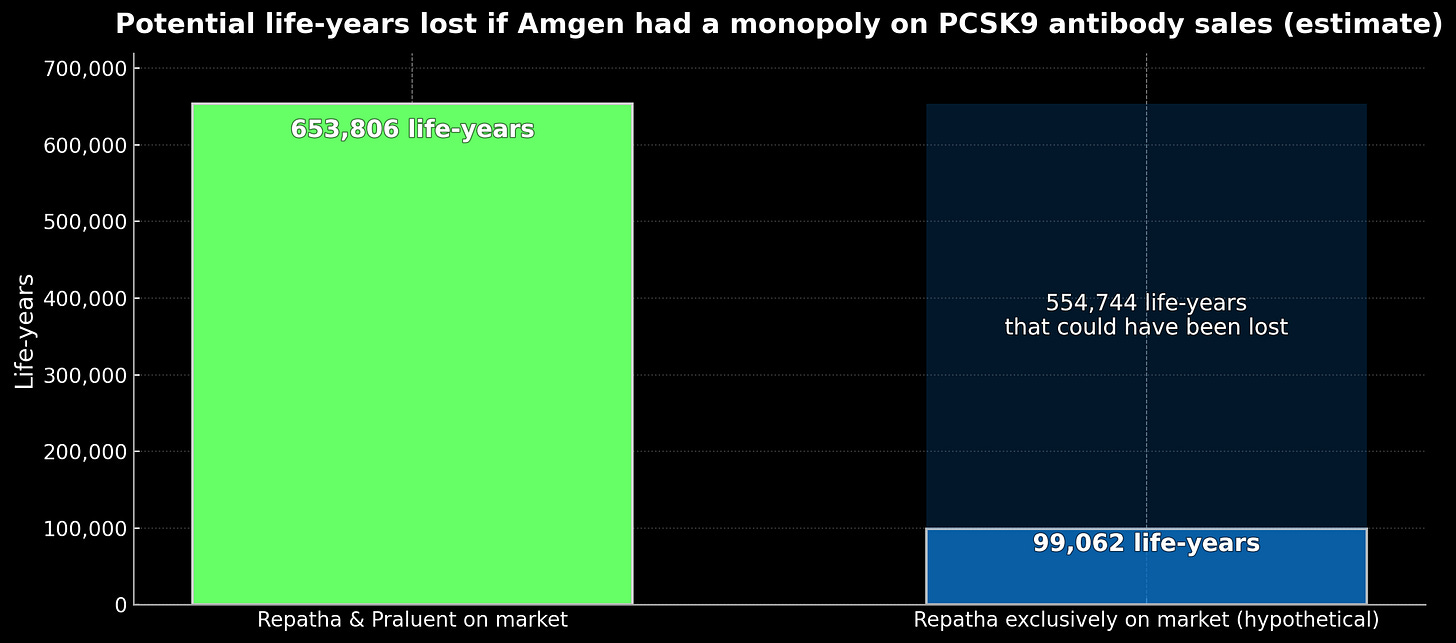

Consider what actually happened versus what Amgen sought. In reality: both drugs launched at fourteen thousand dollars, competition cut prices to fifty-eight hundred, and usage jumped from half a percent to over three percent of eligible patients. New RNA-based approaches emerged with twice-yearly dosing. Under Amgen’s target monopoly: prices would have remained near fourteen thousand dollars indefinitely, fewer than one percent of patients would have received treatment, and alternative approaches would have faced years of delay. Crude modeling suggests this could have prevented a gain of ~550,000 life-years4 over a decade:

The Supreme Court rejected Amgen’s overreach through the enablement doctrine: you must teach what you claim. The Court understood that allowing target-wide monopolies based on minimal disclosure would transform biological mechanisms into winner-take-all territory, collapsing innovation into patent races rather than scientific competition.

This exposes the core policy tension: rewarding genuine pioneers while preserving the competition that benefits patients. Solving it requires preventing patent overreach while actively promoting breakthrough innovation.

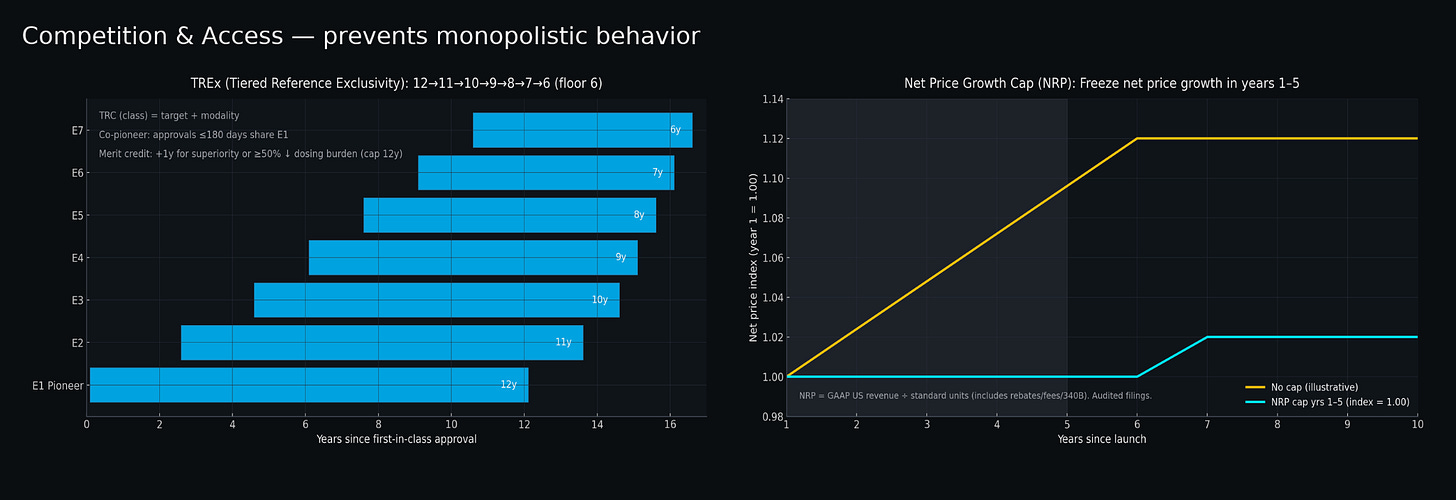

For preventing overreach, tiered exclusivity periods for FDA biosimilar approvals could serve as an automatic check against monopolistic behavior when new biologics enter the market. Rather than granting twelve years of market protection to all biologics regardless of entry order, a tiered system would give pioneers the full twelve years while first followers receive eleven years, second followers ten years, declining to a six-year floor5. This creates pricing pressure from progressively shorter exclusivity windows—companies developing follow-ons must offer genuine added value to justify positive returns on shorter exclusivity periods, while pioneers face earlier competitive pressure that incentivizes proactive price cuts rather than indefinite monopoly pricing.

A net price growth cap represents a separate powerful mechanism: freezing net price growth for all biologics during their first five years post-approval6. This could prevent coordinated price increases that undermine price competition, even when multiple products exist.

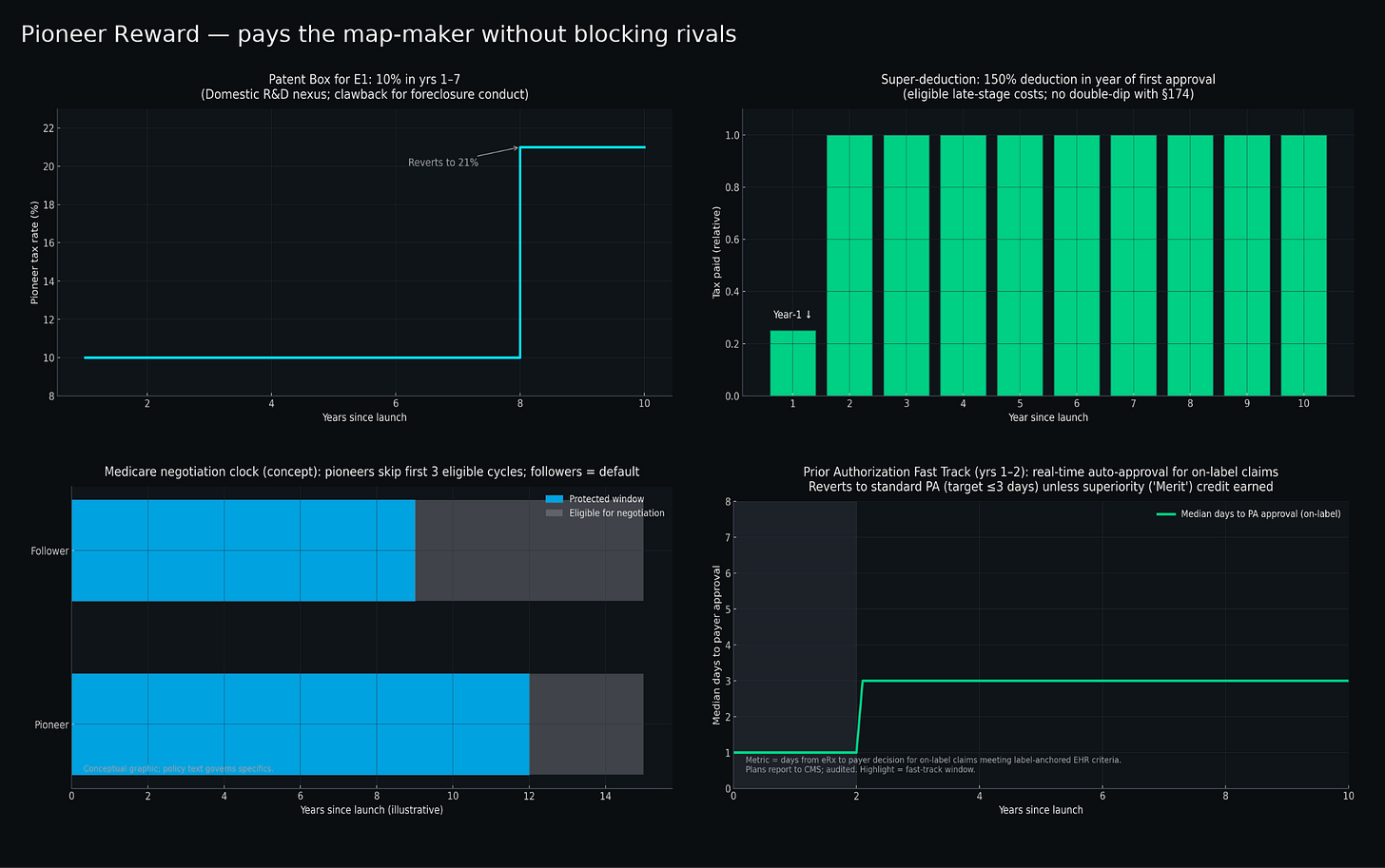

For promoting innovation, tax-based incentives could offer a cleaner approach than extended exclusivity periods. Patent boxes——already implemented successfully in countries like the UK and Ireland——provide reduced corporate tax rates on intellectual property income. Applying this concept specifically to first-in-class biologics could offer rates of ten percent instead of twenty-one percent on qualifying profits for seven years. This could substantially boost early cash flows when pioneers need capital most, without affecting pricing or delaying competition.

Super-deductions allowing enhanced write-offs on late-stage development costs provide another front-loaded incentive. Rather than gambling on extended market exclusivity, companies could claim 150% deductions on qualified clinical trial and manufacturing expenses in their first year post-approval—immediate tax relief that rewards successful execution of risky projects.

Additional targeted mechanisms could include temporary prior-authorization relief for genuine first-in-class therapies and delayed Medicare price negotiation timelines that acknowledge the greater risks pioneers face7.

These approaches hold promise because they address the root problem: current patent law provides identical protection regardless of genuine contribution, creating incentives for companies like Amgen to pursue defensive intellectual property litigation. By front-loading rewards for authentic risk-taking while preserving competitive dynamics, we eliminate the economic logic behind target-wide patent strategies.

Future pioneers will need to earn their kingdoms rather than simply declaring them. That may be exactly as it should be. After all, the combination of innovation incentives and competitive dynamics has produced an unprecedented expansion of human health and longevity. The challenge is preserving both elements through policy design that recognizes economic realities while defending principles that have served us well for centuries.

Amgen’s sales advantage also stemmed from earlier outcomes data—their FOURIER trial reported in May 2017, fifteen months before Sanofi’s ODYSSEY results—and from a larger U.S. sales force. But the legal cloud over alirocumab magnified every other disadvantage.

Incremental EV beyond baseline Repatha profits in a no-Praluent counterfactual.

Inputs:

Formula:

Base case parameters:

EV ≈ $268.9m.

VVV calibrated from the Repatha−Praluent global net-sales gap multiplied by Amgen’s non-GAAP operating margin as % of product sales (≈51.5% in 2022) to proxy profit per $ of sales.

Litigation cost lines reflect AIPLA medians (single-digit millions) and are included for scale.

Regeneron/Sanofi too. Bear with me for a bit.

Estimate based on Kazi et al., JAMA 2016 supplement (eTable 10).

Inputs:

U.S. ASCVD cohort size: 8,531,000

Total incremental life-years with PCSK9 inhibitor therapy for full cohort: 19,812,300

Access deltas from a 2015-2019 EHR study: new PCSK9 starts among eligible ASCVD patients 0.5% in 2015 vs 3.3% by 2019.

Calculations:

Lifetime LY per treated patient derived as 19,812,300 ÷ 8,531,000 ≈ 2.3224

Praluent & Repatha on market: 8,531,000 × 0.033 = 281,523 LYs

Repatha only: 8,531,000 × 0.005 = 42,655 LYs

Lifetime LYs:

Praluent & Repatha on market: 281,523 × 2.3224 ≈ 653,806 LYs

Repatha only: 42,655 × 2.3224 ≈ 99,062 LYs

Difference in LYs between scenarios: 554,744 LYs

Requires amending PHSA §351(k)(7) to authorize Tiered Reference Exclusivity (TREx). FDA would establish Therapeutic Reference Classes by target + modality (e.g., “PCSK9-binding monoclonal antibodies”). Anti-gaming rules include co-pioneer status for approvals within 180 days and merit credits (+1 year, capped at 12) for demonstrated clinical superiority or ≥50% dosing burden reduction.

Net Realized Price defined as GAAP product revenue ÷ US standard units, incorporating all price concessions. Quarterly reporting to CMS with audit authority. Anti-circumvention provisions prevent value-shifting through device fees or non-price remuneration.

Pioneers could, for example, be exempt from Medicare negotiation selection for the first three eligible cycles. Exemption(s) lapse if HHS OIG determines foreclosure conduct within therapeutic class.

This was such a great read - problems clearly articulated with an amazing case study and some practical solutions at the end. Love it!

Enjoyed this read. Very curious that Amgen was able to remain the market leader in this space too. The subtle quip in the industry is that Amgen is a lawfirm disguised as a biotech company, and this story is a great example.