A Better Proxy Than the Rat and Dog

How Axiom Bio is trying to fix drug safety testing.

Disclosure: This profile was commissioned by Axiom Bio. The company provided access to its offices, team, and partner meetings and reviewed drafts for factual accuracy.

Consider the hepatocyte. It is a polyhedral thing, roughly twenty micrometers across - a speck of biology responsible for most of the chemical processing in the human body.

If you could shrink yourself down and step inside, you would find no open floor plan. The interior is a scene of claustrophobic efficiency. The cytoplasm is crammed with the crinkled ovals of mitochondria and the vast, studded pleats of the endoplasmic reticulum, layered tight to maximize the surface area for chemical reaction.

In a healthy liver, these cells stack together in plates, forming the banks of the sinusoidal channels where blood flows. Every Tylenol you swallow must pass through this chemical gauntlet. Mr. Hepatocyte decides what stays and what goes.

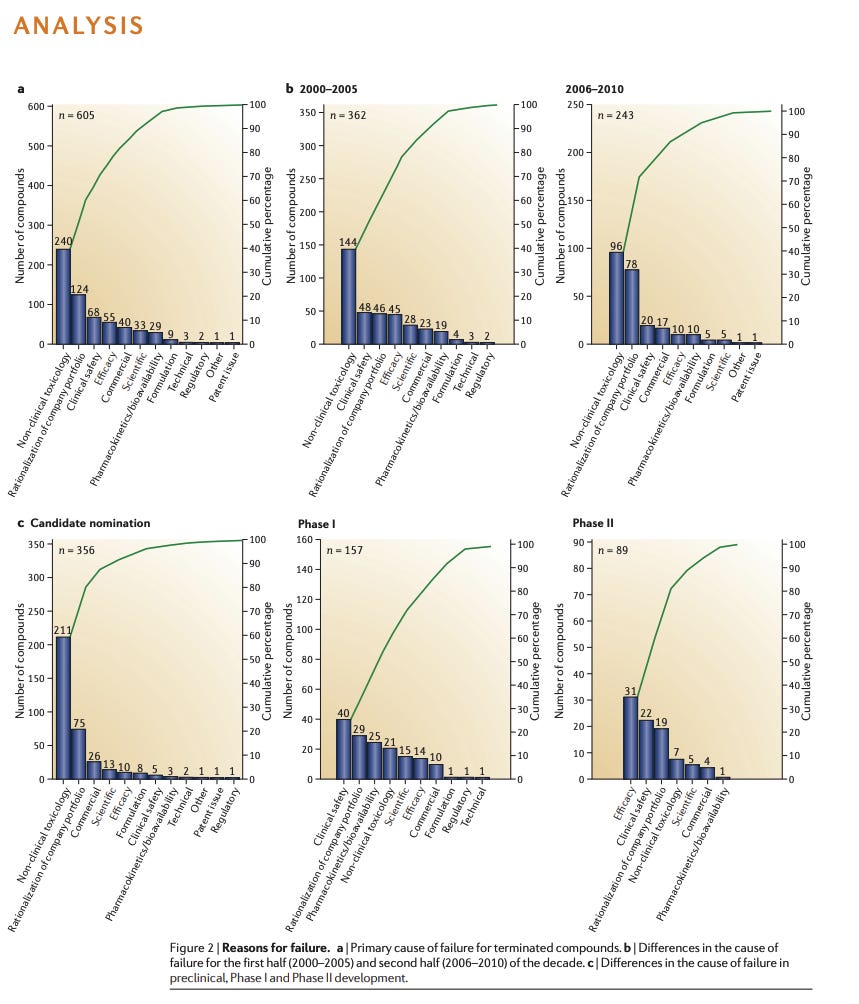

Most pass safely. But some do not. Some drugs trigger a rapid, unstoppable cascade of biochemical dominoes to fall: causing the cell to stress, to swell, or to tear itself apart. This is a fundamental gamble of drug development: and for fifty years, we have tried to predict this catastrophe by feeding drugs to rats and dogs. But a rat is not a human, and a dog is not a miniature man. Biology is eccentric, and when we rely on proxies, we often guess wrong.

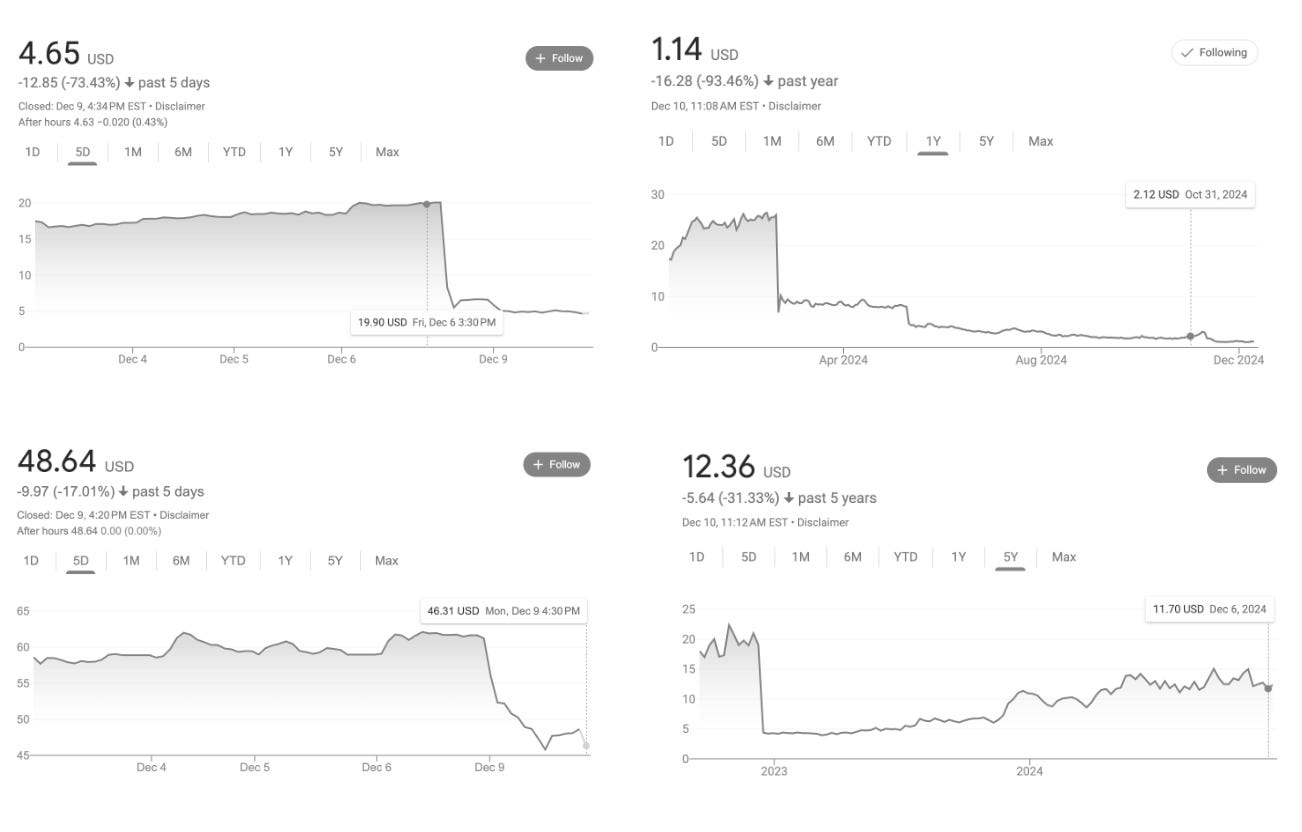

The cost of those guesses is specific and large. In a single month in 2024, liver toxicity flagged three major drugs, wiping out $5 billion in market value in a single week (1, 2, 3).

Of the recent failures, Pfizer’s lotiglipron and danuglipron offer a stark example. The drugs were promising candidates for the lucrative obesity market until mid-stage trials revealed elevated transaminases - enzymes that leak into the bloodstream when liver cells die. That, for Pfizer, was enough. They scrapped the molecules.

And these drugs are far from being an outlier. Hepatotoxicity remains the leading cause of drug withdrawals. Even the medicines that make it to market often do so with caveats: in 2020 and 2021, 60 percent of newly approved drugs carried warnings about liver toxicity on their labels.

In a second-floor office in San Francisco’s South Park, a company called Axiom Bio is attempting to stop guessing. They are betting that the best way to predict what a drug will do to a human liver is to ask the liver itself.

To a visitor, the room reads as a standard software studio, a grid of monitors and ergonomics that could belong to any tech company in the neighborhood. But the work here requires a reminder of the physical world. In one corner sits a climate-controlled vivarium that houses two poison dart frogs, Phyllobates terribilis. In the Colombian rainforest, these frogs are lethal; their skin secretes batrachotoxin, a neurotoxin so potent it can stop a human heart. But here, they are harmless. Their toxicity is borrowed, sequestered from a specific diet of beetles and ants they eat in the wild. Denied those beetles, they are benign.

What’s true of the frogs is true of pharmaceuticals: toxicity is not a fixed property. It’s a relationship between a substance and a context.

The founders of Axiom don’t look like toxicologists. Brandon White is a seven-foot-tall software engineer with a background in machine learning from early Uber. His co-founder, Alex Beatson, is a Princeton PhD who once built a spreadsheet to calculate the net present value of his job offers; the model told him to go into high-frequency trading, but he ignored the math to focus on applying machine learning to the natural sciences.

The team includes biologists from Stanford and data scientists from Citadel, and various defectors from pharma R&D. Together, they share a diagnosis: the AI drug discovery field spent a decade obsessing over “discovery” - finding molecules that bind to proteins. But discovery was never the bottleneck. The bottleneck is prediction: knowing what a molecule will do once it’s inside a human body.

Why AI for Bio Has Failed (So Far)

Suppose you want to double your number of bestsellers. You hire a consultant, and they suggest that since every book requires pages, the solution is to mass-produce blank notebooks.

An editor would correctly identify this as a category error: you are solving the easy logistics problem to avoid the hard creative problem. But for the last ten years, this is essentially the thesis statement of the entire techbio sector. They built a really, really efficient paper mill.

That realization was thick in the air when I visited Axiom’s office. Ruxandra Teslo’s autopsy of AI drug discovery was circulating through the sector. The piece was brutal. Billions of dollars had been raised on a premise that turned out to be wrong, and Teslo had the receipts.

The premise went something like this: Drug discovery is slow because humans are slow. If we could just automate the process of finding molecules that bind to proteins, we could churn out cures the way Amazon churns out packages. Companies like Recursion, BenevolentAI, Atomwise, and Exscientia raised enormous sums on this theory. They built robotic labs. They trained neural networks. They generated molecules by the thousands.

The trouble is that pharma was already drowning in molecules. Warehouses full of molecules, libraries of targets, filing cabinets of hypotheses nobody had gotten around to testing. What they lacked was any reliable way of knowing which molecules would work inside a human body.

The mills worked beautifully; their output was prodigious. But because the industry focused on volume (stationery) rather than validity (writing), the results were nigh disastrous. In the past few years alone, BenevolentAI’s lead candidate failed in Phase 2, and Recursion’s drug for cerebral cavernous malformation showed safety and did nothing else detectable. Between five and eight billion dollars in market value evaporated as the industry remembered, once again, that a molecule which binds to a target in a tube has a long way to travel before it becomes a medicine.

The generous interpretation is that these companies were solving the wrong problem. The less generous interpretation is that they were solving the easy problem, because the easy problem is easier to sell to investors.

In 2025, a fleet of new and advanced generative models have arrived. They can dream up a hundred thousand novel molecular structures in an afternoon. But invention has become trivially cheap. This is like announcing that, having failed to produce any bestsellers with your paper mill, you have decided to build a bigger paper mill. The expensive part was never the stationery. The expensive part - the “translation gap” - is knowing which of those hundred thousand molecules will help instead of harm. It remains as wide as ever.

The Visual Language of Distress

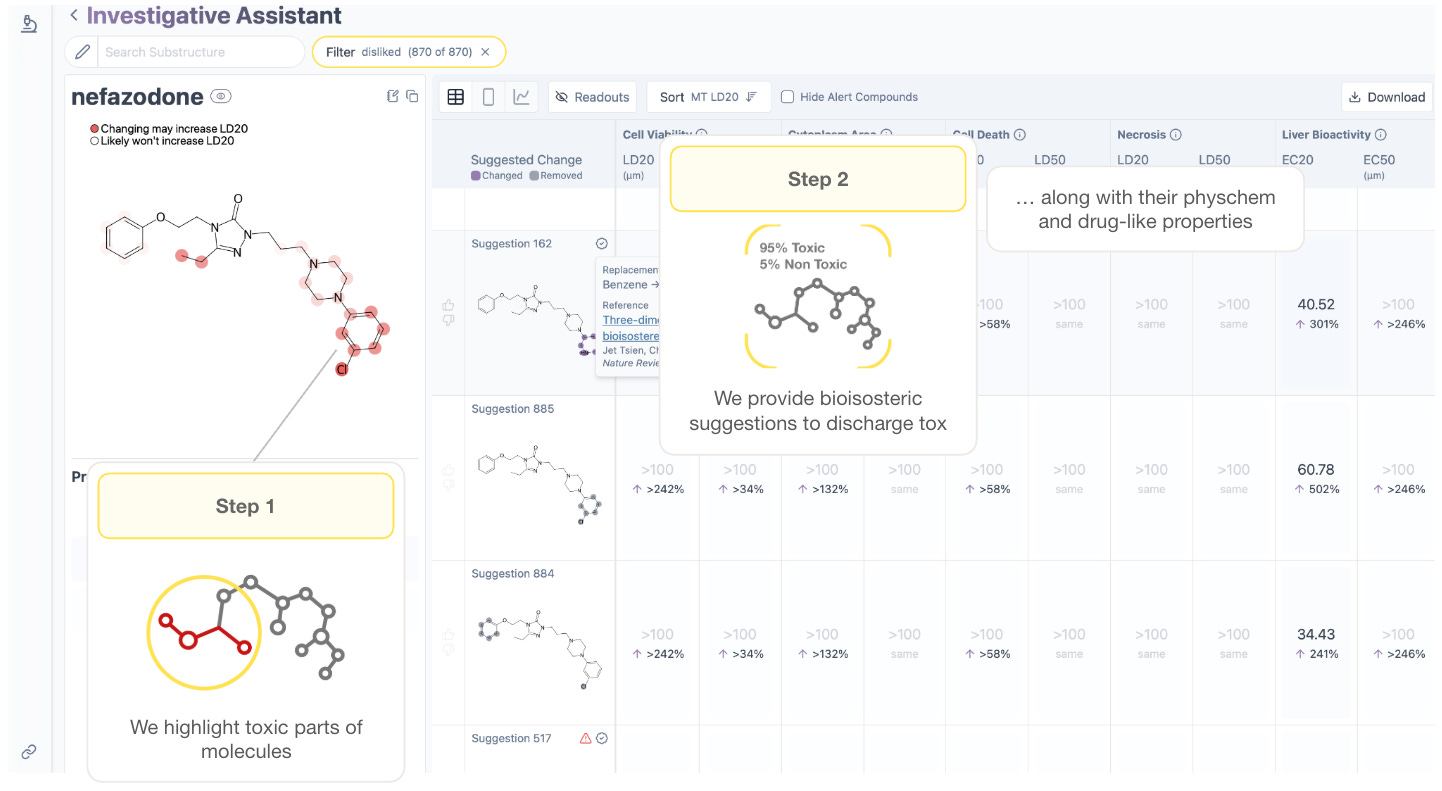

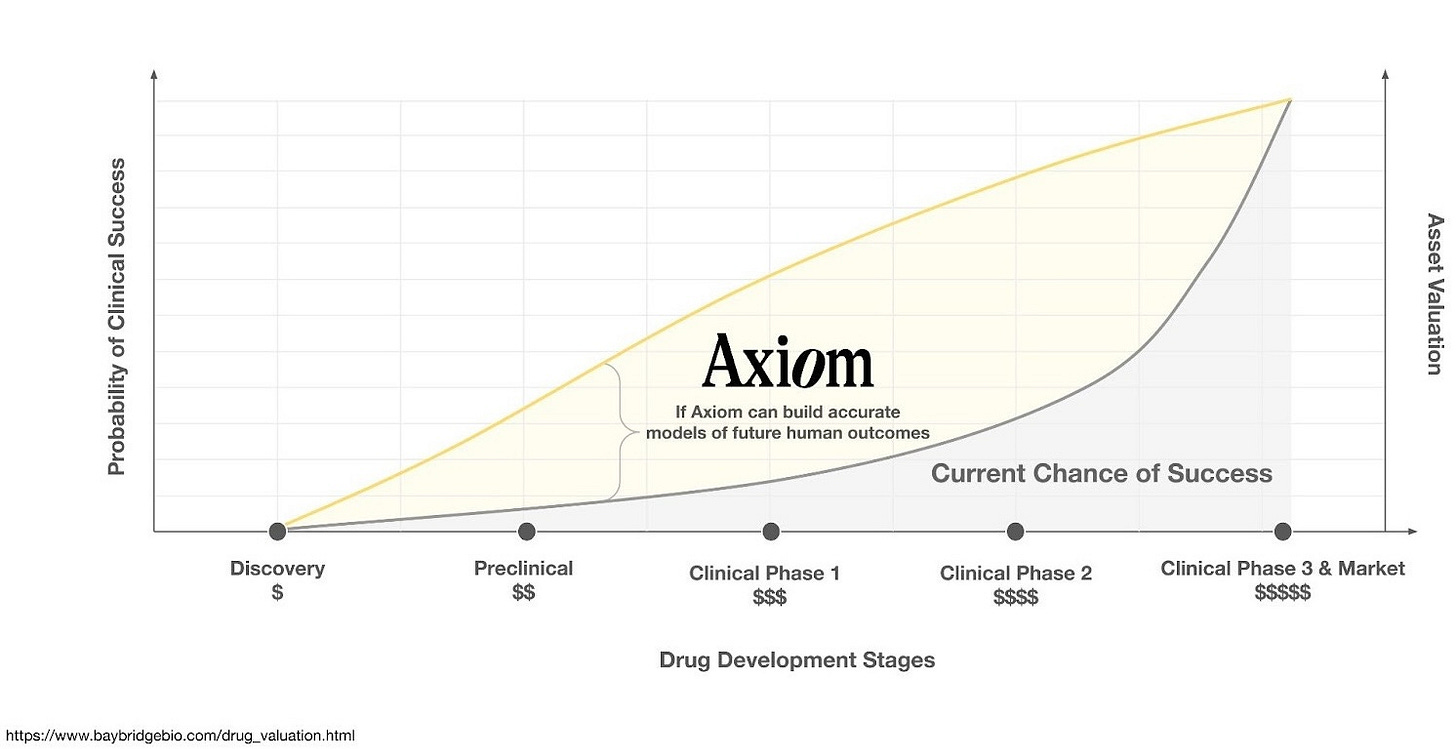

Axiom wants to give drug hunters a flashlight. If a chemist can see why a molecule is toxic - if they can weigh the benefit of a drug against the specific risk of mitochondrial stress or lysosomal swelling - they can design around it. They can fix the flaw before the drug ever leaves the whiteboard.

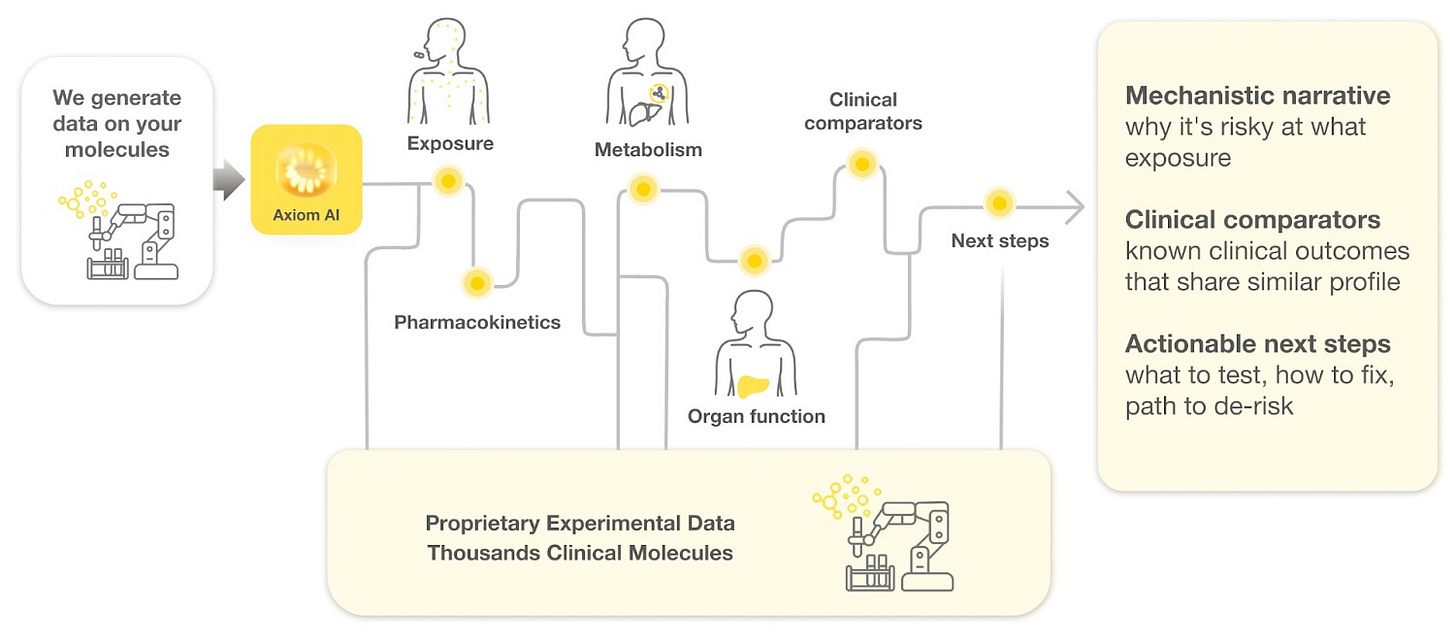

The foundation of this flashlight is a bet on the “scaling laws” of artificial intelligence. The theory holds that if you feed a model enough data about a drug’s exposure, metabolism, and effect on organs, it will eventually derive the fundamental rules of human safety, just as language models derived the rules of grammar.

“We’re trying to find out if the scaling laws for human toxicity exist,” Beatson says, “and whether we can write them first.”

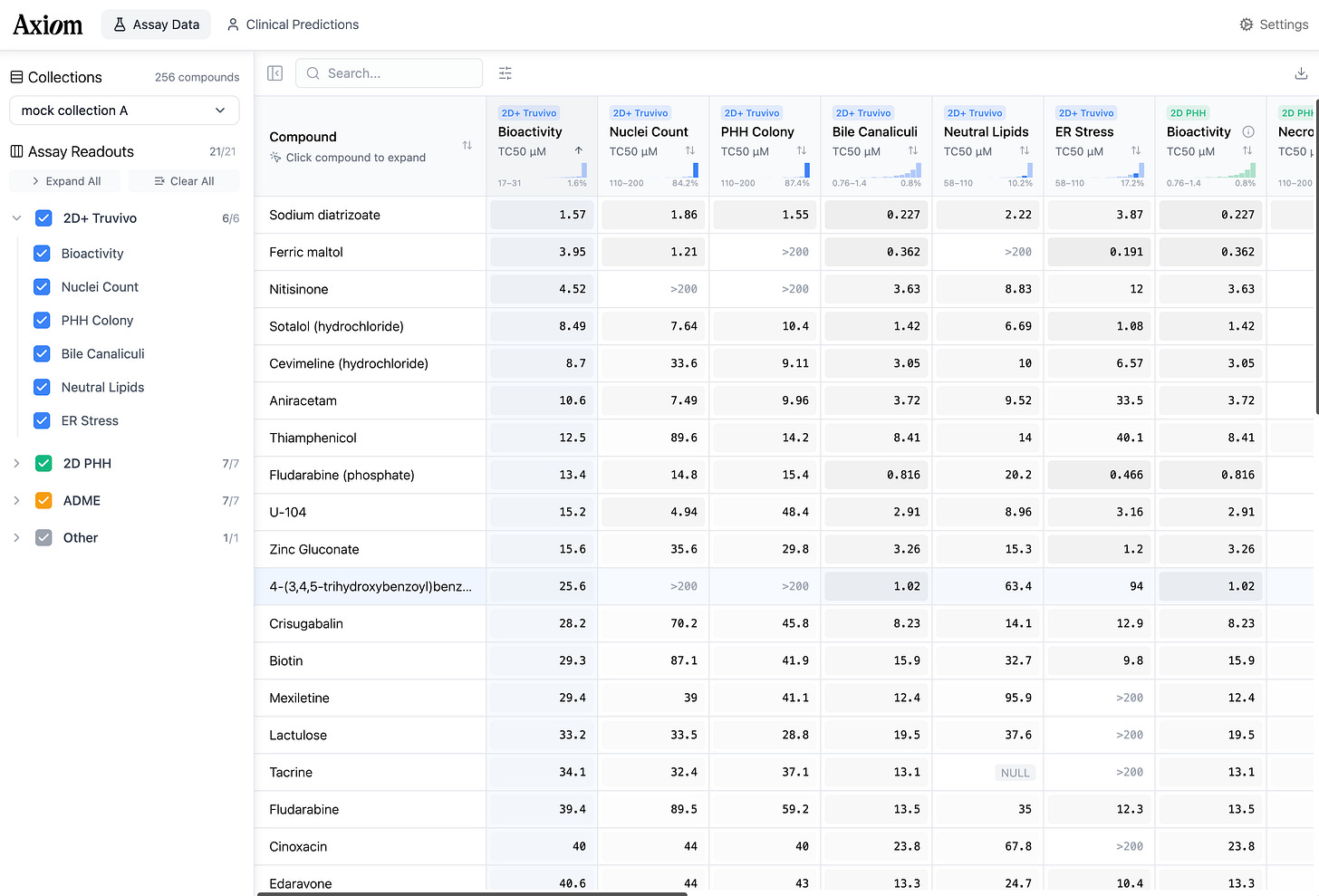

To apply those laws, the team is building a “reasoning agent” connected to a suite of custom tools and massive reference datasets specifically designed for human safety and exposure. The ambition is to move beyond a simple red-light/green-light for toxicity and create a model that acts as a warning system for toxicity in human trials. By parsing the entire corpus of Axiom’s proprietary data - from exposure to metabolism to organ biology to human clinical outcomes - the model constructs a structured reasoning trace, comparing the new candidate to tens of thousands of well-studied historical drugs from Axiom’s experimental dataset; in order to walk the drug hunter step by step through the why behind a prediction.

To feed these models, the team had to industrialize biology overnight. Producing the necessary training data required running eight distinct experimental modalities across thousands of molecules - an effort so massive that vendors, used to the polite pacing of academic research, had never seen anything like it.

The validity of Axiom’s method is perhaps best viewed through the lens of a forensic reconstruction.

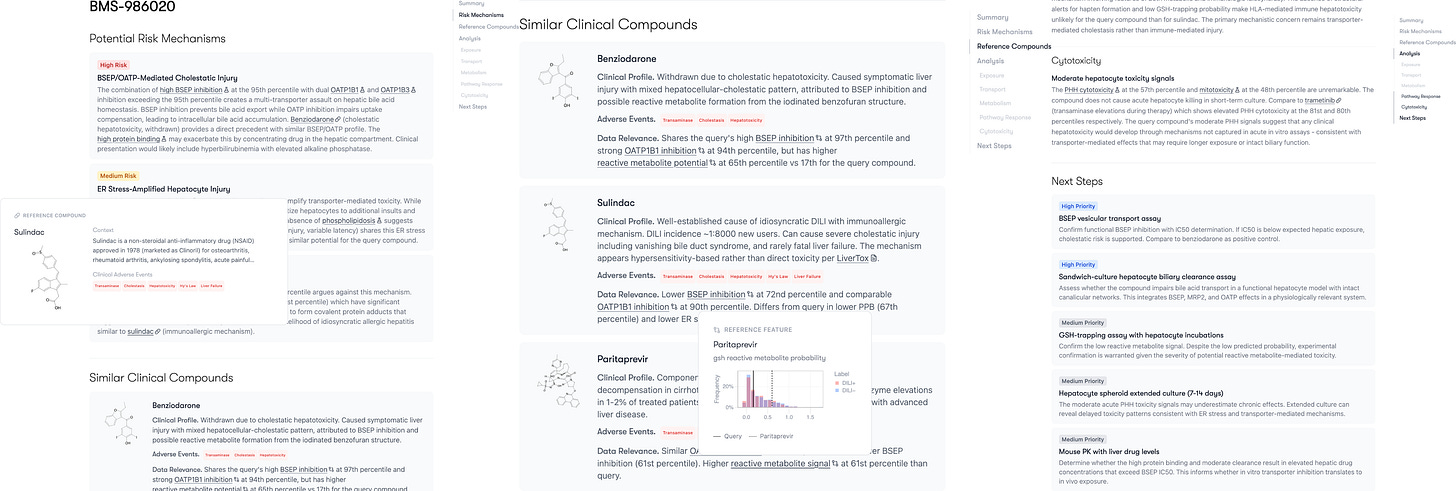

The team points to BMS-986020 as a pivotal example of how its reasoning model could save programs before it’s too late. This molecule was an antagonist of lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (LPA1) - developed to treat pulmonary fibrosis. In Phase 2 trials, it showed efficacy, but in 2016 it was terminated due to causing hepatotoxicity in some patients.

In a blinded simulation, Axiom shows BMS-986020 to its reasoning model. It has no prior knowledge of its identity.

Working solely from Axiom’s internal assay data, the model traced the drug's exposure and metabolic path de novo. It successfully identified the mechanism of toxicity that human researchers had missed, cited relevant clinical comparators, and outlined the specific steps required to confirm the signal. Impressive indeed.

Had this capability been available during the drug’s development, the toxicity concerns could have been addressed before BMS spent tens of millions of dollars on clinical trials.

Latent Signals

Before any of this could work in silico, someone had to keep the cells alive in order to generate the data for the models. Primary hepatocytes - cells taken directly from a human donor - are notoriously fragile. Removed from the body, they panic. They lose their enzymes; they forget their function. Katherine Titterton, Axiom’s founding biologist, spent weeks coaxing these cells to accept their new reality, refining the delicate recipe of their automated protocol until she and the Axiom team could keep them stable and functioning long enough to measure a drug’s effect.

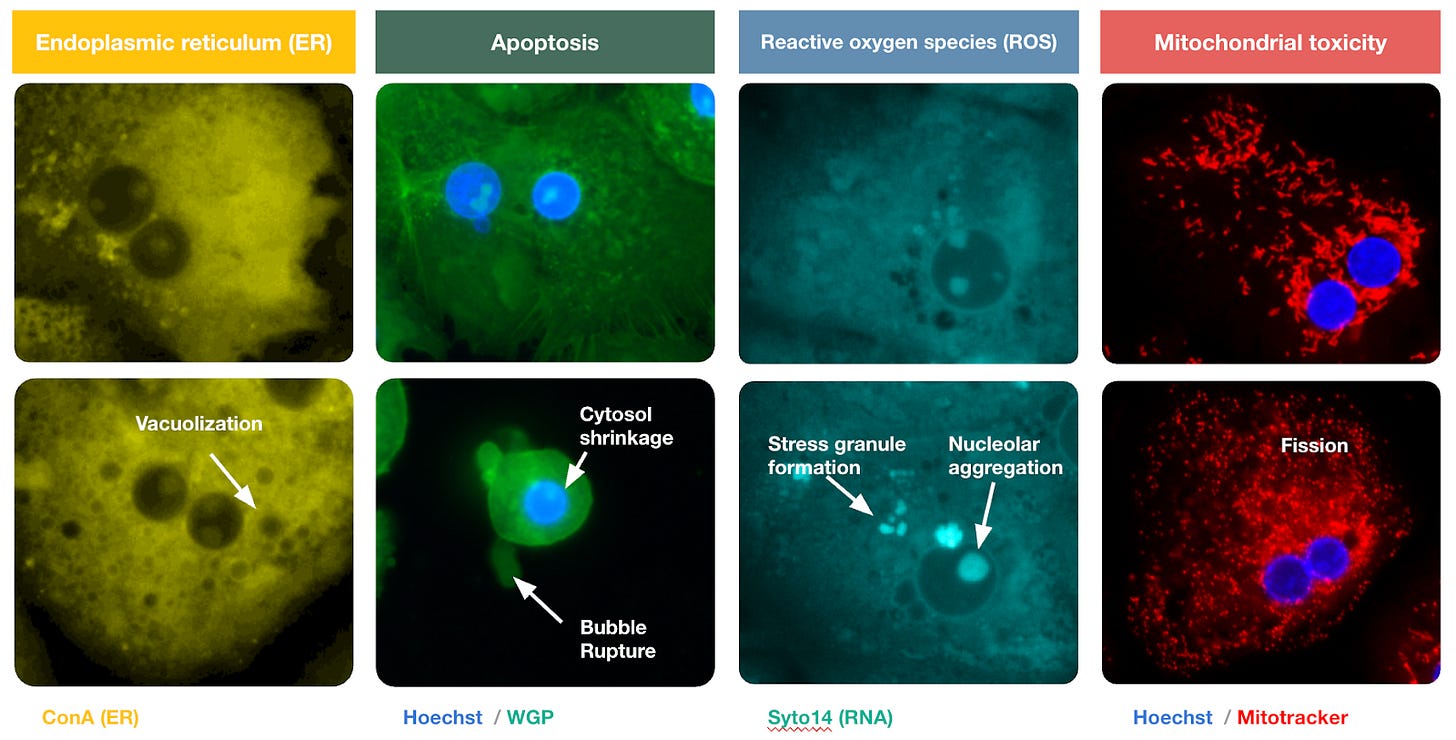

With the hepatocytes finally domesticated, the interrogation could begin. At scale, Axiom exposed these delicate cells to thousands of molecules, staining them with dyes that target specific organelles. Hoechst stain turns the nucleus a vivid blue. MitoTracker makes the mitochondria glow. The result is a technicolor map of the cell’s internal machinery. The membrane, cytoskeleton, and endoplasmic reticulum appear in sharp relief, distinct against the black void.

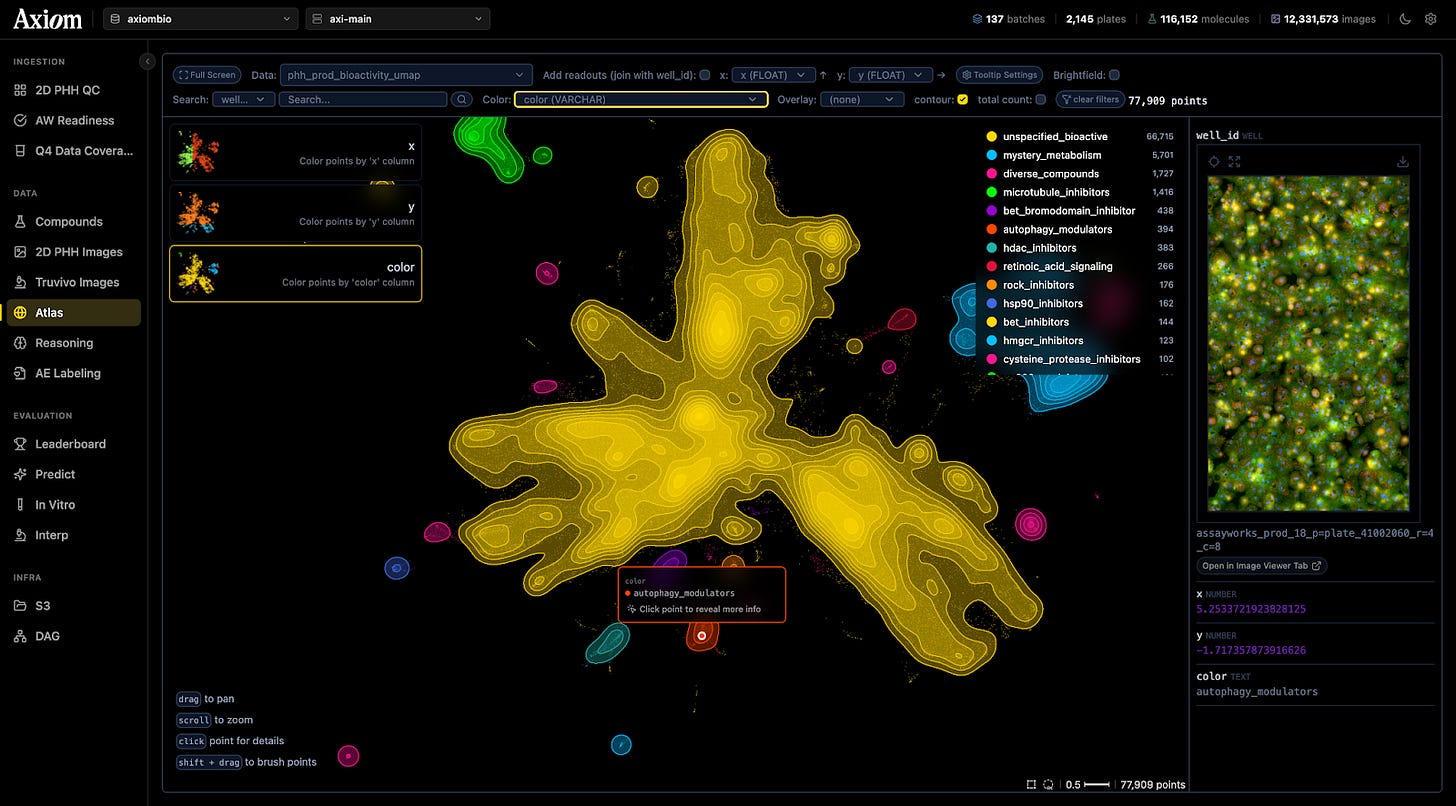

This effort culminated in a library of ten million images showing cells in various states of damage. To the human eye, these images are beautiful, abstract art. To the predictive models Axiom has built, they are training data. Neural networks analyze these images, looking for “phenotypic fingerprints” to learn - subtle changes in the cell’s shape and texture that signal trouble - learning a library of warning signs they can use to judge the safety of novel molecules.

Titterton shows me a cluster of dots on a map of this data. Chemically, the drugs here look nothing alike. But biologically, the images reveal they are doing the exact same thing: the cells look pocked and lunar, their interiors riddled with holes.

These holes are vacuoles. The cells are undergoing autophagy - literally “self-eating.” Standard tests would mark these cells as ‘alive’ because their membranes haven’t ruptured yet. But the damage is already done. They’re going to die. Their AI can see it; and conventional toxicology assays cannot.

But vacuoles are textbook. What about the failures nobody has categorized? To catch what human eyes miss, the team developed a ‘bioactivity algorithm’—a neural network designed to notice what human researchers wouldn’t think to look for.

Traditional toxicology tests look for a single smoking gun. This system measures something finer - small changes in the cell’s texture and shape that occur at low concentrations, before a human researcher would notice anything wrong.

“I have a feeling that there are many ‘unknown unknowns’ that lie beneath,” says Nishkrit Desai, one of Axiom’s machine learning engineers.

Nadeem Karmali, a data scientist who previously worked at Citadel, echoes this sentiment. He sees Axiom’s future through the lens of quantitative finance. He argues that the pharmaceutical industry is currently where Wall Street was forty years ago: awash in data it couldn’t interpret. Back then, early quants learned to predict market volatility by aggregating “weak” signals - disparate, noisy inputs like weather patterns or credit card swipes - that seemed useless individually but were predictive when layered together.

Axiom is applying this logic to biology. A slight change in cell shape here, a minor metabolic shift there - on their own, these are weak signals. But when you aggregate them across a drug’s entire lifecycle - accounting for exposure, metabolism, and organ biology - they build a composite picture of human risk.

Karmali acknowledges that this composite may not be perfect from day one, but he argues that the shift in methodology is what matters.

“Early quantitative finance models were wrong but useful,” he tells me. “They created epistemological bedrock. Even imperfect mechanistic understanding changes how you approach problems.”

To reach that bedrock, the team had to redesign the very architecture of their lab models. Standard liver cells in a dish form a flat, lonely layer that barely resembles a real organ. Axiom’s solution resembles something like a “flattened spheroid” - human liver tissue pressed into layers just enough so a microscope can peer across multiple layers of different cells.

Crucially, this isn’t just a monoculture of hepatocytes. It is a microscopic ecosystem, populated by the hepatocyte’s natural neighbors: Kupffer cells that act as immune sentinels, stromal cells for support, and endothelial cells that line the blood vessels. This complexity allows the cells to survive for weeks at a time, revealing the “slow-burn” toxicities that simpler tests miss. But even a perfect model of the liver is useless if you don’t understand how the drug gets there. A drug is a traveler: it enters the body (exposure), gets broken down into new molecules (metabolism), and finally interacts with the tissue (response). Axiom’s data maps every step of this journey.

Axiom’s platform uses all this data to calculate the human “therapeutic index” - the vital safety margin that dictates a drug’s fate. This is the measured distance between the dose that heals you and the dose that harms you. By quantifying this gap across the drug’s entire lifecycle, the system provides a precise estimate of risk, along with a mechanistic narrative which explains the “why” rather than a mysterious red flag.

The Long Game

For decades, pharmaceutical safety has worked like this: we feed drugs to rats and dogs until we find the dose that kills them, then we work backward to guess what might be safe for humans.

History suggests that biology is not nostalgic. In the 1970s, testing drugs for bacterial toxins meant injecting them into rabbits and waiting for a fever. Then came the LAL test, which used the copper-rich blue blood of the horseshoe crab to detect the same toxins with greater precision. And so the rabbits were retired.

Axiom is betting that AI is the next LAL.

To see why that bet might pay off, you have to go to Phoenix, Arizona, where the American College of Toxicology held its annual meeting. Axiom’s booth looks like it wandered in from a different conference. I watch the team pitch a toxicologist from a major pharma company. She stands with her arms crossed, lanyard dangling - but she’s here, at the booth, which means something is already not working for her. She admits she has a molecule giving “worrisome signals.” Her internal testing cycle takes a month. When the team explains they can provide high-dimensional data that actually explains the ‘why’, she starts asking questions. How many compounds? What endpoints? How robust?

This is the conversation Axiom was built for. The toxicologist doesn’t need to be sold on the problem. She lives the problem. What she needs is a more accurate answer she can trust.

In early 2026, Axiom will complete blinded studies with several of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies. The predictions are on the table. If they’re right - if the platform can reliably predict human exposure and flag human toxicity before trials begin - the implications are hard to overstate. Fewer failed drugs. Fewer patients enrolled in trials for medicines that were never going to work. A clearer signal, sooner, about which molecules to back.

Now they wait. In the office in South Park, nobody’s biting their nails.

Hmm, the disclaimer at the bottom definitely made something click for me regarding the hype-y tone..

It would've been nice to see some comparisons with competitors: what are e.g. Cellarity, or Emulate Liver-Chip doing? They're closing higher accuracy on DILIrank than Axiom, for example

Nice article. I assume the next step for Axiom (or a similar company) is to develop models that have some predictive validity for clinical efficacy. That would be a more challenging project given the multiplicity of organ types and effector systems to mimic. But the POS stats are pretty brutal and the trajectory is not going in the right direction.